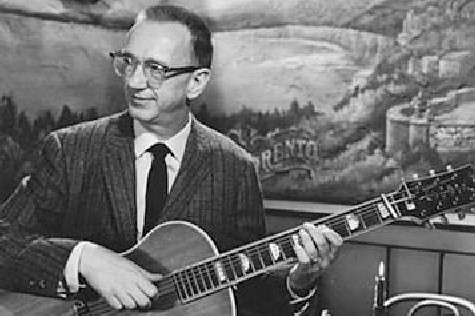

One of my all-time favorite guitarists is the late George Van Eps (1913-1998). Van Eps, born in Plainfield, NJ, and son of popular banjoist Fred Van Eps, grew up around music. Not only was his father a noted musician, but his brothers were also professional musicians. His mother was an accomplished pianist. As a child growing up during the era of Prohibition (1920-1933), his father became well-known among fellow musicians for his high-quality “hootch,” and his house was often filled with members of the Paul Whiteman Orchestra among others. George remembered being bounced on frequent visitor George Gershwin’s knee.

At age 12, after suffering a bout of rheumatic fever, he had to leave school, and began playing banjo, but his life was changed when another famed visitor, jazz guitar pioneer Eddie Lang, left his Gibson L-4 in George’s care for several days. Over those few days, the twelve year old transitioned from a banjo player to a guitarist. His father arranged for George to get a guitar and get lessons. He practiced and practiced until his fingers literally bled.

By the time he was in his mid-teens, he was playing professional gigs, and continued to enhance his skills. By his late teens, he began working with the top New York-area dance bands, and rapidly achieved a reputation as a reliable and skilled player. As time went on, he turned into a formidable soloist, though in those days, without amplification, his intricate solos were seldom heard in a live setting, and only somewhat better heard in recording sessions, where, if he was lucky, he might get 16 or 32 bars for a brief solo.

In 1934, he held the rhythm guitar chair in the Benny Goodman Orchestra, but didn’t keep it long, due to constantly receiving the famous Goodman “ray” for taking harmonic liberties with the charts.

By the early 1930s, he became a top endorser for Epiphone, which, along with D’Angelico, were among the few makers of fine guitars that were worthy competitors to Kalamazoo, Michigan’s Gibson Guitar Co. George normally played the top-line Deluxe model, which was prominently displayed in Epiphone ads. He taught a number of top rhythm guitarists his techniques. One of his finest students was Allan (“Picking for Patsy”) Reuss.

While touring with the Ray Noble Orchestra in the later 1930s, after moving with the band to southern California, Van Eps began experimenting with the concept of the guitar as a “lap piano,” but found its range too limiting. He eventually came up with the idea of adding a seventh string, an “A”, below the bottom “E” string (an octave below the fifth string) to fill out the lower register. He also formulated a new way of playing which permitted him to intertwine lead, rhythm, and bass lines, often simultaneously, where all seven strings are integrated fully into his playing.

By playing a conventional six-string guitar where he changed the first through sixth strings to the second through seventh (the second or “B” string now occupied the top position), he developed his new playing style, much of it with his fingers, rather than a pick, though without amplification, this style was reserved for studio work rather than public performances. He was then ready to have the Epiphone factory build a prototype seven-string instrument which validated his experiments. He then brought his beloved 1933 Epiphone Deluxe to Epiphone’s New York factory to have the neck removed and replaced with one configured for seven strings. This was his main instrument until the late 1960s.

He left Ray Noble’s orchestra and joined famed Hollywood arranger Paul Weston’s orchestra, which was extremely busy in the studios and film stages. He stayed with Weston until WWII came along, when he, also a skilled machinist, moved back to New Jersey to help his father and brothers with a small machine shop business that supported the war effort. After the war, he returned to California with his family, and resumed his work with Weston’s orchestra. In 1949, he recorded several sides as a leader, playing mostly original tunes, on the Jump label. His Jump sides as leader and as sideman are available today. Studio work was mixed with work with Weston, as well as with small jazz-oriented groups and occasional club dates. He appeared in Jack Webb’s movie Pete Kelly’s Blues, and in 1956, he recorded his first album as leader, Mellow Guitar. Accompanied by members of Paul Weston’s orchestra, this was Van Eps’ introduction of the seven-string guitar to the world. He designed and built his own pickup which allowed him to play in the more popular amplified style, and which also allowed him to more effectively perform in studio and small group settings. This album was very critically acclaimed and was a staple in most guitarists’ record collections, for good reason. The intricate chordings and multiple voicings were the culmination of all he had learned in almost 25 years of professional playing. Through the efforts of members of Paul Weston’s family, Mellow Guitar is again available on the Corinthian label as an LP, and on the Sundazed label as a CD.

Several years after Mellow Guitar was released, Van Eps again retired from the music business to run a very busy hobby shop in southern California. During this time, he built, by hand, a fully working steam locomotive at a very small scale. Eventually, he sold the business and went back into the financially lucrative studios.

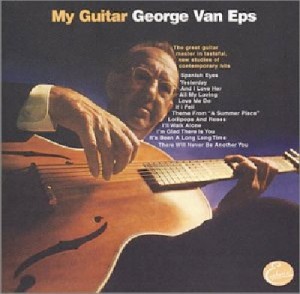

In 1967, he recorded the first of three groundbreaking albums for Capitol Records. The first, My Guitar, received superior reviews, and prompted the Fred Gretsch Guitar Company to develop a variation of their popular Country Club model guitar as either a sixor seven-string instrument, appropriately named the “George Van Eps model.” The follow-up album, George Van Eps Seven String Guitar from 1968 also received high acclaim from reviewers and fans alike. Because Capitol Records was also the licensee of records by The Beatles, the label insisted that George include several of their tunes on his records. He did a pretty amazing job finding things in tunes like “All My Loving”, “Love Me Do”, and others on which to improvise. In the case of “Love Me Do,” it was almost unrecognizable, due to Van Eps’ extensive reharmonization of the tune. His accompaniment on these first two albums was by Frank Flynn, another veteran of the Paul Weston orchestra, who played the marimba, vibraphone, and brushes. Frank’s backing was minimalistic, keeping out of Van Eps’ way as much as possible.

His final Capitol album, Soliloquy, was played completely solo, and would have been a fitting end to anyone else’s career, but not for Van Eps, though he didn’t know it at the time.

Around this time, my uncle, former Gibson/Epiphone clinician and later regional sales manager for CBS/Fender, Andy Nelson, was involved with a popular band camp somewhere in the midwest. He had arranged for Van Eps to do a brief performance. As usual when you have a line of top-flight musicians doing clinic-type performances, schedules have no bearing on reality. When it was Van Eps’ turn to play, he began an intricate reharmonization of some old chestnut from the Great American Songbook, and let time get away from him. Some of the kids in the audience began to fidget (in the mid-60s, if it wasn’t rock and roll, kids didn’t want to hear it). The stage manager was on his way onstage to ask Van Eps to wrap it up when Andy, all 5’6″ of him, stepped into his path and told him “you’ll have to get through me first.” Andy may have been short, but he was also very solid and could look menacing if he wanted to, and it was no act…trust me… This is the respect and awe most guitarists held for George, who, being a very modest and unassuming man, continually poo-poohed.

For much of the 1970s, he spent most of his time writing a three-volume encyclopedia of his method, called George Van Eps’ Harmonic Mechanisms for Guitar, published by Mel Bay. This series of books was not a progressive method, per se. They are more a collection of lessons and techniques that can be studied in any order at any time, with such things as moving lines in tenths, in opposite directions. Not for the faint at heart or unlimber of fingers. This is truly a collection of knucklebusting lessons for the advanced player. As the books were published to yet more critical acclaim, his beloved wife, Kay, passed away, after which he lost his desire to play.

In the mid-late 1980s, he finally began practicing again, only to suffer a guitarists worst nightmare, a broken hand. He was already in his seventies at this point, so it took a long time for the bones to heal to a point that he could resume practicing. One thing that made it somewhat easier for his damaged hand was tuning his guitar down a whole step, so the high “E” was now a “D”, and the low “A” was now a “B”. This did not create a problem for him to assimilate. When he was playing every day, he would challenge others to detune any one string of his guitar. Within seconds, he was able to compensate and include that now detuned string into what he was playing without breaking a sweat.

In the early 1990s, he was just about ready to resume public performances when he was asked by record producer Carl Jefferson (founder of the Concord Jazz label) to record a duet album with fellow guitarist Howard Alden. The 1994 recording “Thirteen Strings” demonstrated to the world that even though he was now in his late 70s, George Van Eps was back and hadn’t lost a thing. By the second of four duet albums with Alden, Howard was sufficently influenced by Van Eps that he switched to the seven-string guitar himself, and remains a practitioner to this day. Sometime after the fourth duet album, Concord Jazz label owner Carl Jefferson was in a bit of a quandary. Famed guitarist Johnny Smith had recorded twelve short solo pieces and had told Jefferson that there would be no more, but there wasn’t enough to put out a CD, as the total time was less than 30 minutes. Jefferson approached Van Eps and asked that he record an additional twelve solo pieces. The album, Legends, was a fine swan song for both players and again demonstrated that age had not diminished either player’s skills.

The remaining years until his death at 85 from pneumonia in 1998 were triumph after triumph. He traveled to concerts as much as his health would allow, and regularly played gigs near his home in Huntington Beach, California. There are few videos of Van Eps playing, save for some brief scenes in the aforementioned Pete Kelly’s Blues, and a clip of him recorded toward the end of his life, playing “I’ve Got A Crush On You” on YouTube.

Fortunately, many of his recordings are still available. The four Concord Jazz duet albums with Howard Alden can be downloaded, DRM-free from emusic.com. Legends is available, though with DRM, at the iTunes Store. Amazon.com’s CD store has the best selection of Van Eps recordings. Along with his Concord performances (the four duets with Howard Alden, and Legends), Mellow Guitar and the Jump compilation (the 1949 sessions) are available.