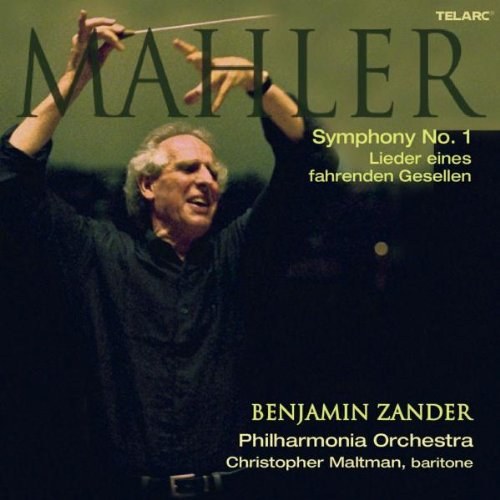

Benjamin Zander returns with another distinguished contribution to his Telarc Mahler cycle, albeit one with less blazing conviction than his ‘Third’, ‘Sixth’, or ‘Ninth’. Initially, the concept of a Zander Mahler traversal may have appeared less enticing than a Michael Tilson Thomas cycle (at least to those not familiar with Zander). In the event, however, the Zander cycle has moved from strength to strength while the Tilson Thomas cycle, after an impressive start, has descended into the realm of sleek technical fetish. Zander, conversely, remains devoted to the emotional impact of Mahler, though this recording finds him more reserved than one might expect… or is it just the mix?

Compared to other versions of Mahler’s ‘First’, Zander makes a good run at getting into the top ten. Top place in my book remains with the reigning champion for over thirty-five years now, Jascha Horenstein and the London Symphony Orchestra. That Unicorn recording from the late 1960’s was one of Horenstein’s Indian-summer masterpieces, blowing away his earlier Vox recording and pretty much all others. The secret of Horenstein’s strength is that he approaches the work not as a naïve and fresh early piece, but as a full-fledged complex masterpiece. And Mahler’s ‘First’ can take it. Some might find it early Mahler viewed through the lens of the bleak final works, but it is potent. Horenstein is spacious and epic in the outer movements, driven and sarcastic in the inner ones. His funeral march really is too fast, but it is tolerable in light of his ground-shaking finale. The recorded sound is not comparable to the finest modern recordings, of course, but it was decent for its day, and proves quite listenable on Compact Disc. (Of course, if someone were to reissue it in the improved fidelity of high-resolution digital, it would sound that much better, hint, hint.)

One Mahler ‘First’ that consistently floats to the top as I keep listening over the years is the Chicago recording by Claudio Abbado on Deutsche Grammophon. It dated from the early 1980’s and is now hard to find because it was superseded in the DG catalogue by Abbado’s more recent remake with the Berlin Philharmonic. Though the Berlin recording is good – essentially the same interpretation, played more sleekly in a beefier acoustic – it lacks the quicksilver magic of the Chicago recording. The Chicago outing is marred by some odd edits at the beginning of the funeral march (evidently falling back on a rehearsal tape with slightly different microphone perspectives) which are annoying, but overall, it remains one of the finest examples of Abbado’s distinctively deft and poetic way with Mahler, whereas the later Berlin version begins to show signs of the gleaming autopilot that Abbado got stuck in during the 1990’s.

One of the best Mahler ‘First’s’ is just now returning to the market in a box set: Gary Bertini and the Cologne Philharmonic on EMI. The Israeli conductor’s rendition was caught on tour live in Tokyo’s Suntory Hall in 1991, but those familiar with Bertini will know that there is no grandstanding or playing to the gallery. Bertini “just” does the work as written. But considering the complexity of detail in the scores of Mahler symphonies, this is a feat so astoundingly rare, only a handful of recordings have ever achieved it. Bertini achieves that technical feat, but far more importantly, he achieves it with distinction. By taking Mahler’s ‘First’ seriously and at face value, Bertini ends up finding the same epic vein as Horenstein (albeit with less sheer rhetoric). EMI is reissuing Bertini’s Mahler recordings in a box set commemorating the masterful but relatively little-known conductor who passed away in 2005. That box will be essential for all Mahlerians.

Bruno Walter’s well known stereo recording from around 1960 remains essential listening for its warmth and flexibility. Though far less epic than many (including his earlier monophonic recording with the New York Philharmonic), this Columbia recording (now available from Sony) remains treasurable for its open-heartedness. The ‘Third’ movement, in particular, finds Walter in potent territory. Quite simply put, no one has ever matched Walter in this movement. He encourages his players (the so-called “Columbia Symphony,” consisting of top-notch Hollywood free-lancers, Los Angeles Philharmonic regulars, and some ringers from the New York Philharmonic) to spring rhythms quite independently of the bar lines in an astonishingly free and liberating style that makes other performances seem stiff and pedestrian in comparison. In the last movement, Walter lacks the noise and fury of most of his rivals, but carries the movement forward quite effectively on the strength of his emotional commitment. Overall, some things are smoothed over, and many details of the score are scarcely noticed, but it remains a great performance, caught in good sound for the period. Walter’s earlier Columbia recording (in monophonic sound) features more firepower than the stereo recording, but it still features the same genial rounding of some of Mahler’s more aggressive moments, a fact which led Mahler’s daughter Anna to publicly express her preference for the Mahler performances of William Steinberg. Both the early Walter and the Steinberg recordings popped up on compact disc a few years back, and are interesting listening for Mahler aficionados.

Somewhat similar to Walter’s lyricism is the warmth of Czech conductor Rafael Kubelik, who played up the rural, folksy aspects of the Mahler symphonies, in both his Deutsche Grammophon cycle, and in the live recordings from the late 1970’s and early 1980’s which have been popping up in recent years on Audite. In general, I prefer the later live recordings, because they feature a greater depth of sound from the Bavarian Radio Symphony, and are recorded far better than most live ventures from this period. Kubelik remains a favorite of most Mahler fans, and it is the one most often cited as a top choice by those who have doubts about Horenstein’s epic approach.

Another “vintage” Mahlerian was Sir John Barbirolli, who recorded Mahler’s ‘First’ with the Hallé Orchestra in 1958 for Pye. That record was released in monophonic sound, but an experimental stereo version was made at the same time, and when the John Barbirolli Society (with Dutton Laboratories) reissued the recording on Compact Disc, they used the stereo master. It is distinctly early stereo, pretty gauche by modern standards, but it does open up the sound-world of the recording effectively. Barbirolli’s concept of the piece emphasizes its shifting moods, creating a strong profile. The playing of the Hallé Orchestra displays more enthusiasm than polish, but then again, I’ve grown so tired of the empty perfectionism of modern orchestras that I find the Hallé quite refreshing, warts and all, because they play with emotional commitment.

No discussion of great Mahler would be complete without a reference to the Mahler ‘First’ recordings by the great Leonard Bernstein. His New York Philharmonic recording was made in the 1960’s, and it has enormous vitality. In his enthusiasm, Bernstein has a tendency to exaggerate and underline his points with a great deal of rhetoric, but the performance remains thoroughly magnetic. His Deutsche Grammophon remake from the 1980’s with the Concertgebouw Orchestra exaggerates the exaggerations even further, though much of the conductor’s compelling vision remains. It is often remarked that the early Bernstein recordings are fresh but inexperienced, whereas the late Bernstein Mahler outings are overdone as Bernstein searched for new meaning in the scores. Perhaps the ideal solution is to pick up the DVD-Video set of Bernstein conducting the Mahler symphonies with the Vienna Philharmonic in the 1970’s. His performance there is closer to the impetuous New York recording in speed and manner, but with the added warmth of the Viennese orchestra’s playing.

But how does Zander fare against such august competition? Not bad at all, although the recorded sound here seems to be a rare Telarc misstep, falling below the lofty standards of earlier recordings in this series. Setting aside the live recording of Mahler’s ‘Ninth’ which was independently produced and only later released by Telarc, Zander’s Mahler cycle has been made as studio recordings in either the Walthamstow Assembly Hall or the Watford Coliseum. I don’t know if there is a particular logic to which hall is used for each piece, or if it is merely a matter of scheduling, but Watford has the livelier acoustic of the two, whereas Walthamstow seems to offer more width than depth in its soundstage. The problem with Watford, though, is that it is a dangerously boomy acoustic, the kind of space that can sound notably different on different days just because of the air pressure or outside temperature. Whether it be weather or not, the sound of the hall this time around is noticeably less clear than in the recordings of the ‘Fifth’ and ‘Sixth’. My first thought was that perhaps the lack of inner clarity here was caused by Mahler’s scoring, but though a relatively early work, the ‘First’ is still remarkably sophisticated in its scoring. And a quick comparison of the scores of the ‘First’ and ‘Fifth’ shows that the latter work was far more densely scored, yet it still sounds out more clearly than the earlier work does here.

Upon closer inspection, it sounds as if the microphones have been placed farther back than they were for those earlier recordings, or perhaps it is just the balance of the surround-sound mix. Perhaps the goal was to change the amount of sound coming through the rear channels in the multichannel program, but whatever the case, the extra distance gives the aural impression of a foggy veil of sound rising up between the orchestra and listener. Could this be caused exclusively by humid weather? Or could it be that there are certain resonance points in the building that are hard to avoid? I have no idea, but I can certainly say that it mutes the color and vigor of the performance taking place on the other side of the veil. This boominess persists throughout, slightly dampening bass response when the low instruments play softly, and then ringing too resonantly when they play loudly. The timpani have retreated to the distant back of the sound stage. Even the horns have to struggle to float up over the acoustic soup. Whatever causes it, this fog of reverberation is something that pops up every once in a while on recordings in this venue, regardless of engineer or company.

The slight haze of the recorded sound mutes the colors of Zander’s vision of the first movement, a vision which is already tempered by the knowledge that the movement is based on an earlier Mahler song which carries undercurrents of sorrow beneath its bright surfaces. Thus, Zander restrains the movement from building to as boisterous a peak as Abbado, for instance. With a little less fog on the landscape, Zander’s approach would stand alongside Horenstein’s, but that graying of the colors gives the movement an almost autumnal pall. Zander argues in his accompanying comments for skipping the first movement repeat, which he does indeed leave out on this recording. His point is well-taken: It was added much later as an afterthought by Mahler, who was attempting to make what was originally billed as a “symphonic poem” look more like a symphony. He is quite correct that the repeat does not sound inevitable when it is included and that it compromises the dramatic structure of the movement. I can’t disagree with that. The one problem, though, is that without the repeat, the later movements seem to outweigh the early part of the symphony by a lopsided amount. This could be offset by performing the original version of the symphony, which in addition to featuring some changes in orchestration, also includes a reflective interlude originally placed as second movement, called “Blumine.” Without “Blumine,” though, the early part of the symphony just sounds too short.

Zander is effectively still in the heart of the first movement, where the bottom drops out and the music reaches a transfigured state of near timelessness, but his finest moment comes later in the movement, when Mahler gradually turns his vision of nature’s paradise into a nightmarish negative image. Zander is one of the very, very few conductors who notice that as this passage grows louder and louder, with shorter and shorter note values, Mahler actually says in the score to get slower and slower. Horenstein, Bertini, and Eschenbach were among the few previous recordings to get that detail correct, but they are now joined by Zander. Everyone else either stays at the same speed or even speeds up. When the passage is done correctly (and Zander does it even better when it reappears in the finale), the effect is almost fractal: As the volume grows inexorably louder, the notes keep subdividing into smaller and smaller units, yet the tempo itself gets slower, even though the activity level is getting more and more frenetic with every bar. When performed correctly, the passage is almost unbearable, and the release which follows is almost manic.

The second movement finds Zander in bumptious high spirits, steering the Philharmonia through Mahler’s foot-stomping ländler at a vigorous, well-sprung clip (quite a world away from the self-consciously lumbering renditions by Bernstein, Eschenbach, Maazel, and Kondrashin). In the country-waltz trio, Zander encourages the players to use rubato and be flexible, without descending into micro-management of the musical line. It is also nice to hear that in the closing sections of the scherzo, Zander doesn’t treat the “Vorwärts” sections as new tempos. Rather, he merely begins pressing literally “forward” in the current tempo, leading to the acceleration at the scherzo’s end.

Mahler directed for the third movement to be played “Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen” (“Solemn and measured, without dragging”). That qualifying afterthought has provoked many conductors (including Bernstein, Horenstein, and most recently, Sir Roger Norrington) to play the movement fairly quickly, sarcastically. Again, Zander is mindful of where the music came from: It includes sections lifted almost literally from another song in Mahler’s lovesick “Songs of a Wayfarer.” Thus he correctly detects that the prevailing mood here is less one of mockery than it is one of bitter sorrow. The opening double bass solo is presumably performed by Neil Tarlton, who is listed first in the section in the included roster of players. One cannot fault the technical finish of his playing. Instead, though, one wishes that he would characterize the solo more, that he would – to borrow a phrase from Frank Zappa – “put some eyebrows on it.” There is an old tradition of playing this solo “ugly,” intentionally out-of-tune and homely, but the player here instead chooses to save his dignity at the expense of musical potency.

The finale opens grandly, at a surprisingly spacious tempo, considering that Zander’s timing is less than twenty minutes for the movement. In the first interlude, though, it becomes evident where the time is made up. Though Zander can usually be relied upon to jump off into the byways of Mahler symphonies with the glee of an explorer, he here seems more concerned about holding the episodic movement together. Heaven forbid that he should start worrying about his dignity now, too! After missing the ardor that Horenstein finds in that interlude, Zander perks up with a blazing attack into the middle part of the movement, picking up enough energy to blow away the shadows and fog. The rest of the movement continues to grow in intensity (although, again, a bit rushed in the quiet interlude), leading to an exciting assault on the closing pages, finally blazing in the vintage manner for which Zander’s fans adore him, and which no recording can completely compromise.

Preceding the symphony on this disc is the ‘Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen’ (‘Songs of a Wayfarer’), the musical source for much of the symphony’s mood and material. Christopher Maltman gives a fine performance of the songs, not hesitating to commit to the extreme lovelorn moods essayed here. Perhaps he could convey a touch more vulnerability by opening up his voice when the lines go up higher, but his manner works effectively enough. My one big complaint, however, lies again with the recording. Having heard Mahler songs live in concert, I know full well that Mahler was rough on singers, always placing his orchestrations right on that line where they could drown the soloist out if he or she doesn’t project vigorously. So I have no great complaint if a little judicious miking of the soloist is done in recordings to help him stay afloat in a vast sea of orchestral sound. But to have a reasonable room perspective on the orchestra mixed together with a “close-up” of the singer doesn’t cut it in my book. Part of the problem is that the initial recording was done this way, and then when the multichannel mix was made, it brought the spotlit voice even further out into the room because of its three-dimensional perspective. So here the surround sound mix exaggerates an already exaggerated recording perspective. Blame pop music, I suppose, because even the regular Red Book layer of this hybrid disc has a more spotlit singer than any older recording I listened to for comparison (Fischer-Dieskau, Hampson, etc). Classical recordings have been getting more and more “pop” like this in recent years, relegating the composer’s vision further and further off into the rubbish bin of quaint notions. But Mahler is one composer who knew exactly what he wanted. If he had wanted his songs to sound like the singer was standing in the front row while the orchestra was at the back of the stage, he damned well would have told them to set up in exactly that configuration.

The surround mix may well be part of the problem in the symphony, too. I found that the “veil” effect was lessened when I switched to the stereo-only layer of the super audio content. Switching over to the stereo Compact Disc layer flattened the aural image a little, but still the veil seemed less. Moving back to the 5.1 multichannel mix, I found that if I sat in front of the normal focal spot of my sound system, the veil was a little less blurry. It seems that a slight increase of basic microphone distance (compared to earlier recordings in the series), combined with a slightly over-enthusiastic use of the rear channels creates the acoustic fog here that slightly obscures the efforts of conductor and orchestra. In the end, this is not a “deal-breaker.” I wouldn’t let it stop anyone from buying this disc who likes Zander’s approach. It can be helped with a movement in your seating position, or even just by turning your speakers a touch rearward. Those without surround sound capabilities will probably merely find the recording slightly on the boomy side. In other words, I’m splitting hairs, because Telarc is one of the finest in the business, and we expect the best from them.

In the end, I would rank this disc in the top ten recordings of Mahler’s ‘Symphony No. 1’. A little more clarity in recorded sound and a little more frisson from the conductor and orchestra might have brought it into the top handful, but it stands respectably as it is. Zander fans and Mahlerians will find this release compulsory, but even general listeners new to Mahler should keep in mind that all of Zander’s Mahler cycle on Telarc comes accompanied by a free discussion Compact Disc where Zander talks about the music and presents excerpts to illustrate his points. These lecture discs are valuable, persuasively-written guides that help both novice and grizzled veteran more closely understand Mahler and the composer’s performers, too.