Joseph Anthony Passalaqua was born in 1929 at New Brunswick, NJ to an Italian-American working class family. He showed musical promise at an early age, so his father pushed him very hard to practice for as much as 6 hours a day and all day on weekends and holidays, as he saw his son’s talents as an opportunity to escape the poverty of this industrial New Jersey city. Jpe’s skills grew and grew, so by his early teens, he was performing regularly at Sons of Italy and Knights of Columbus gatherings, as well as weddings and other social events in his community. In his mid-teens, he quit school and got jobs as guitarist with a number of bands including Tony Pastor’s big band. As he got older and began working on the road, he unfortunately acquired a number of bad habits, as did many traveling professional musicians of the time, the worst of which was an addiction to heroin.

He continued to play in various settings throughout the United States, but as his addiction worsened, it got harder and harder to get work. Throughout much of the 1950s, Joe was in and out of jail and drug rehabilitation facilities, finally winding up in federal prison for several years. That experience was sufficient for him to really want to make a change in his life, and wound up in the communal Synanon residential rehab facility in California. While many rehabilitation programs discouraged their patients from going back to environments where they could get back into the same life they had before, Joe was able to convince his counselors and doctors that music was all he knew, and that he truly had no intention of resuming those bad habits. Several other residents of this facility were also musicians. Some old, battered instruments were obtained, and as they were physically healing and learning how to live the life of the straight and narrow, Joe and his fellow addict/ musicians were working to get their “chops” back so they could earn a living once they left the Synanon group. Joe remained with this group for several years. By the early 1960s, a record producer heard these Synanon residents performing somewhere and brought them into the studio. A record album, The Sounds of Synanon was released on the Pacific Jazz label to great critical acclaim-especially for Joe Pass.

Joe got a record deal out of this, and recorded additional albums for Pacific Jazz and World Pacific, including Simplicity, Catch Me, Django, and other lessstellar efforts such as an album of the music of the Beatles, played on a 12-string guitar. These albums got him steady work in jazz clubs and even more lucrative studio work. By the early 1970s, the owner of a Lincoln-Mercury car dealership in Concord, CA, Carl Jefferson, got Joe and fellow guitarist Herb Ellis to record several albums on his new Concord Jazzrecord label. Thanks to a decent distribution deal, these recordings on Concord Jazz could be found in large numbers of record stores, and sold quite well. After two or three albums with Concord Jazz, Joe and Herb left to join record producer Norman Granz’s new Pablolabel. Norman had previously started and later sold the famed Verve label, and decided to get back into the record business with a stable of outstanding players, including Joe and Herb, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, Oscar Peterson, vibist Milt Jackson, and a number of other “A-list” performers. Granz was a firm believer in spontaneity, and tried to get things recorded in the first or second take (it also meant less time in expensive studios).

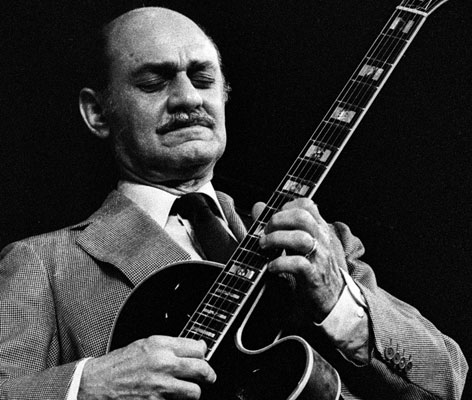

Joe flourished on Pablo. His first recording with Herb Ellis, Two for the Road was an outstanding album that really put Joe in the limelight. My personal favorites on that album were two separate versions of the popular tune Cherokee. The first version was performed at a finger-blistering pace that just took your breath away. The second version was a Doctorate level course in swing. The one album that completely changed things for Joe, and brought him to the very top of the heap, was the album Virtuoso. This was a solo guitar recording, of which about half the tunes, due to a problem with the recording mixer, and a fortunate placement of microphones around the guitar, were released without the presence of an amplifier. Granz, frugal person that he was, listened to the tapes, and had the recording engineer “doctor things” a bit to make the acoustic recordings sound OK, so they didn’t have to go back later and re-record them with the amplifier. Joe used a combination of pick and fingerstyle, conventional fretting, and “hammering on” with his left hand, where the string was “hammered” down to the fretboard instead of using a pick to get the sound out (a technique often used by rocker Eddie Van Halen, and jazzer Stanley Jordan), and combinations of all these techniques. Joe’s career was changed forever. Now, most concert appearances were solo outings, as were most of his many, many recordings on Pablo.

As gifted and as famous as he was, he never seemed to lose his sense of humility with his fans. I saw him in concert three times, and had a chance to chat with him twice. The first time was at a Pablo Jazz at the Philharmonic concert in Miami in 1975. On the bill was the Count Basie Orchestra, Ella Fitzgerald, Oscar Peterson, and Joe Pass. During intermission, I snuck backstage and had a chance to talk to him for a few minutes. He had just received a lovely custom-made D’Aquisto guitar, over which he could not stop gushing. He kept saying he was a “nobody”, and that who I should go and talk to was Count Basie’s rhythm guitarist, Freddie Green, who was setting up for the second act. In my youth (I think I was barely 21 at the time), I just didn’t understand what all the fuss was about with Freddie–he never soloed, and with no amp, you could barely hear him (remind me someday to do a blog about Freddie Green), and skipped an opportunity of a lifetime. I talked to Joe for a few more minutes and returned to my seat before I was asked to do so by Security. Joe signed my program Keep Playing! I still treasure that autograph. I saw him again several years later in Kansas City, MO, where he was performing at a City-sponsored free concert in one of the large parks. Again, he was warm, friendly, unassuming, and self-deprecating. He never seemed to appreciate what an amazing talent he had (more on that in a bit). I saw him for a third time, performing solo at the late, lamented jazz club Bubba’s in Fort Lauderdale. It was at this venue when I saw a different side of him. A group of people were having a good old time, chatting, laughing, and otherwise ignoring Joe. They were so loud that Joe finally stopped and explained that he couldn’t work like this-that he normally filled concert halls, and requested that they just shut up. You could have (finally) heard a pin drop, at least until a number of members of the audience loudly applauded. The rest of the set was more respectful. I was recently in New York at a jazz club, and was disappointed to note that someone had to get on the PA system before the musicians started, to ask everyone to stop talking during the performance. People are so rude!

He was also a great teacher. Toward the end of his life, he recorded a number of instructional videos for Hot Licks, and others, that showcased his amazing talents, and his ability to convey his encyclopedic knowledge, but without a lot of technical jargon. You could sense his frustration and annoyance when he had to explain something in terms of music theory. He said he seldom thought in terms of theory–he just played it.

For a number of years, he was associated with Gibson’s famous model ES-175 jazz guitar (also played by jazzers Jim Hall, Herb Ellis, and rocker Steve Howe), which was modestly priced (back then), and relatively rugged with the body constructed of durable plywood and maple veneers, which was ideal for a musician who spent much of the year on the road, trusting their instruments to airline baggage handlers. By the late 1970s, he signed an agreement with Japanese guitarmaker Ibanez, who came out with the JP-20 model, which Joe played exclusively for a number of years. Toward the end of his life, he signed a similar deal with Epiphone, who still have the Joe Pass Emperor II model in their catalog, though he was most often seen again with a Gibson ES-175 in those last years.

Time went on, and he recorded many more CDs, some on the Telarc label. It was around that time that I heard he had terminal liver cancer. He had just gotten married after many years of bachelorhood, and had to continue working for as long as he could to leave something for his wife, Ellen, who lived in Germany. He recorded a Christmas album Six String Santa among other less-than-stellar projects. His final recording session in May, 1994, was a very unusual one, with country and western performer Roy Clark, where they played the music of 1950s country star Hank Williams. That was his last performance, public or private. Three weeks later, he was dead. Just Jazz Guitar magazine published a special memorial issue a while after his passing, which published anecdotes of his life. One story that had not been widely known was that soon after he was diagnosed with liver cancer, he became very depressed, and began using heroin again (for the first time since he joined Synanon in the 50s). One of his closest friends was able to convince him to give it up for the sake of his wife and his legacy.

Another story was one of the more poignant. Shortly before his death, he became more introspective, and was able to finally come to grips with his incredible talent, stating that it was a gift from God, and that he was grateful for the opportunity to share that gift with others. Here are a few titles I would personally recommend:

- Joe Pass: Guitar Virtuoso, a 4-cd box set containing the best of his Pablo recordings.

- Virtuoso: Where it really all started for him on the Pablo label.

- Take Love Easy: duets with singer Ella Fitzgerald. Simply the best.

- Summer Nights: with rhythm guitarist John Pisano, these are wonderfully relaxed swinging tunes–many of which made famous by Django Reinhardt.

- Intercontinental: an expensive import, recorded just before he hit it big with Pablo, it’s worth every penny.

- Catch Me: recorded in the mid-late 60s as

- he was just getting his career back together.

- Two for the Road: With fellow guitarist Herb Ellis. Just a great swinging session.

- Solo Jazz Guitar: An instructional Hot Licks DVD. His unassuming humor and humanity shines through.

My personal recommendations of individual tunes for the cash-challenged at Apple’s iTunes Store:

From the Virtuoso album:

- Night and Day

- Stella By Starlight

- All the Things You Are

- The Song is You

From the Fitzgerald and Pass Again album:

- You Took Advantage of Me

- The One I Love Belongs to Somebody Else

From the Two for the Road album (with Herb Ellis):

- Cherokee (Concept 1)

- Seven Come Eleven