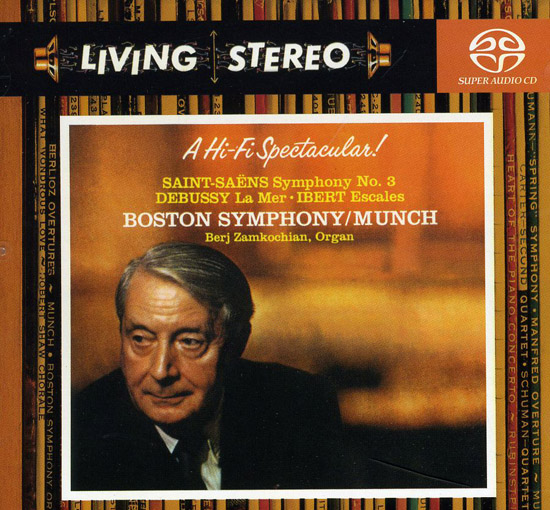

The place where most performances of French composer Charles Camille Saint-Saëns’ ‘Third Symphony’ go wrong is on the podium. For such a well-known and popular piece, it is astonishing how truly few outstanding, idiomatic recordings there have been. I have about twenty recordings in my collection, but I would call only a handful of them worthy performances. What’s even more amazing is to see some of the star conductors who have missed the target completely: Herbert von Karajan, Leonard Bernstein, Eugene Ormandy (at least in his later versions), Jean Martinon, Ernest Ansermet, Seiji Ozawa, Michel Plasson. What most often happens is that the conductor approaches the work as a high romantic blockbuster and attempts to make it as grandiose as possible. But despite the everything-but-the-kitchen-sink feel of the finale, Saint-Saëns’ ‘Organ Symphony’ is actually a lithe work. The composer was responding to the spirit of the times in giving his work a grand, often turgid surface, but at heart, Saint-Saëns was a classicist. Conductors who look for a psychological probing of the depths end up bloating the work with baggage that it shouldn’t have to bear. Those few conductors who see past the stereotype of nineteenth century romanticism and treat the work leanly actually end up revealing for more about this elegant yet elusive composer: His reticence itself speaks volumes. The other perennial problem of successfully performing this work is one of virtuosity. It is an orchestral showpiece, but a potentially treacherous one, to be sure. Many performances obsess about hitting the right notes and thus end up missing the “music” completely. Fortunately, the RCA reissue of Charles Munch’s classic Boston Symphony recording from 1959 brings one of the few insightful recordings of this piece to Super Audio Compact Disc, in three-channel sound.

Munch trumps most other conductors by keeping Saint-Saëns’ rich orchestral textures under control. If the conductor encourages the players to fatten up their tone too much, the whole thing can turn into a heavy-handed, bloated affair, which is grossly inappropriate for a dapper fellow like Saint-Saëns. This is not to say, however, that the finale shouldn’t go over the top: Rather, by design, the finale is perfectly capable of reaching heights of high camp unmatched by any other piece in the repertory. But high-carbohydrate performances that never catch fire have a tendency to implode in those last pages instead of vaulting up to a peak. While Munch avoids the bloated effect, he shows his mixed French and German background by keeping the piece fairly stolid at the end. Indeed, I feel compelled to go against received wisdom, which often has it that Munch’s performance is the greatest recording of this work, period. Though I feel it is far better than most, I find Munch’s approach to the work to be just a little bit too poker-faced, a touch too sober. Munch is at his finest in the first half of the first movement, where he lets the tricky, nervous scoring fall into place on its own, throwing his concentration onto the dramatic ebb and flow of the drama. This leaves a few strands out of place, but the way the music is scored, even the most precise performances end up with this problem, and Munch wisely decided his concentration would pay more dividends elsewhere. No other performance generates as much power in this movement. But for greater excitement in the finale, there are some fine alternatives.

The three performances I prefer to Munch for greater fireworks and excitement in the latter stages of the work are Charles Dutoit and the Montreal Symphony (Decca, 1984), Edo de Waart and the San Francisco Symphony (Philips, 1983), and Paul Paray and Detroit Symphony (Mercury, 1957). The Paray was the main rival to Munch back in the 1950’s, and if the Munch ultimately got the upper hand in critical assessments, it is because of the richer sound of the RCA recording and the more sophisticated playing of the Boston Symphony. Paray’s Detroit orchestra is pleasingly piquant with the brighter, more traditionally French timbre that it bears in comparison to the Bostoners (who themselves have always sounded more French than most other American orchestras). But though the Detroit players under Paray could shape phrases with great character, there is no doubt that Boston was the superior orchestra. Where many high string passages in the slow half of the first movement suffer intonation problems in Detroit, the Boston players rarely lose their magnificent sheen. Furthermore, the Paray is a typically in-your-face Mercury recording, with the organ balanced very closely and very little in the way of hall reverberation. The RCA recording, from Symphony Hall in Boston, was originally a three track affair (left, center, and right) and this hybrid SACD marks the first commercial presentation of the original recorded tracks in that form. The normal stereo master used over the years has been a mixed-down two track version. Fortunately for those who want to keep the sound picture as much like the original record as possible, this SACD hybrid also contains an SACD high-resolution two-channel stereo version. And listeners who don’t have access to an SACD player will be delighted to know that the disc is also playable on regular CD players in standard stereo. Like many early multichannel recordings from the late 1990’s, the 3-channel mix of this recording tends to pull a little too much focus into the center track, leaving the strings somewhat marginalized, but the advantage is that the added focus in the center helps the woodwinds, keeping them from getting buried in a sea of string sound. The stereo mix (both SACD and CD) lowers that central focus and spreads the sound out more conventionally. RCA’s 1959 recording perspective, though closer up than is standard today, allows for more of a sense of space than the rather brash Mercury recording for Paray (which is available itself on standard CD), but the RCA is by no means spacious. And the fact remains that Paray’s performance often has more wink, more wit than the Munch, particularly in the scherzo section of the second movement. Paray goes from breezy to campy with great aplomb, taking risks in a manner that is, frankly, more typical of a Munch performance. Munch here, though, seems more Germanic in his emphasis on dramatic power and sonic weight, particularly in the closing pages of the symphony, where he disappointingly never loosens the reins to let his players sprint for the finish line. It’s a shame that Munch’s 1940’s recording of the work with the New York Philharmonic was before the age of stereo, because it is a more fiery performance.

Returning, momentarily, to the sonic qualities of the Boston Munch recording, the closeness of pickup on the organ does allow for an amazingly rich bass response that even puts many digital recordings to shame. The organ pedals register gloriously, even without a subwoofer channel. The worst problem for the recording, overall, is that its saturation leads to a little distortion in the most crowded parts of the finale. It seems likely that this is a feature of the original recording, for John Newton comments in the SACD booklet that the DSD transfer of the original master tapes was done without equalization or tweaking. Compared against the original vinyl record, it certainly comes out sounding better, as even the finest LP’s of the 1950’s bore extensive equalization and distortion in heavily scored orchestral music. Suffice it to say that the recording comes up sounding pretty fresh in this incarnation, so aficionados of Munch or Saint-Saëns can hardly go wrong, particularly at the competitive mid-level price for which this disc is being listed. But in addition to Paray, there are other options.

Charles Dutoit, though an often fervent admirer of Munch, follows Paray’s lead in the Saint-Saëns’ ‘Third’, whipping up the excitement along the way and not shying away from the composer’s flamboyance. An even more boisterous performance, surprisingly, is the Edo de Waart recording which Philips made in the early eighties. De Waart is hardly a name one associates with boisterous camp, but this recording features the fastest, most high-spirited romp through the finale that I’ve heard, replete with an unmarked acceleration to a new even faster tempo for the fugue that starts in the strings a couple of minutes past the huge organ chords. I haven’t seen the score to Saint-Saëns’ ‘Third Symphony’, but I’m guessing that the new tempo isn’t marked, because no one else does it. But what a refreshing touch! So often that fugue gets bogged down when deployed at the standard tempo. De Waart assures that it keeps vital, so the movement never flags or seems overlong. Whether or not such tinkering with the score is good musicology, it is most certainly good theatre, and it helps De Waart triumph. The Dutch conductor does not secure as idiomatically French a sound as Dutoit or Paray, but for a one-off recording from an unexpected source, it remains delightful, despite a certain glassiness to the early digital sound. The Dutoit recording is like the de Waart an early digital recording, but it comes from the warm acoustic environs of the St. Eustache Church in Montreal. The overdubbed organ track is a drawback, though, sticking out a little unnaturally from the orchestral sound. But all in all, Dutoit’s is probably the best recommendation for great performance with good sound.

Among the grandiose performances, I would cite the finest as being the Berlin Philharmonic performance with James Levine conducting on Deutsche Grammophon, and the Eurodisc recording of Christoph Eschenbach conducting the Bamberg Symphony. Eschenbach is especially arresting in the slow half of the first movement (analogous to the slow movement of a standard four-movement classical symphony), daringly stretching the tempo out to almost the breaking point. Though unconventional, this approach rightly emphasizes that the slow movement is more erotic than religious, despite the attempts by decades of commentators to clean it up by emphasizing the latter. Ecstatic, yes; devotional, in a way; but religious? Not to my ears. The remainder of Eschenbach’s performance is grand, but in an over-the-top manner that makes it more fun than the average run-through. Those familiar with the scrappy-sounding ensemble that the Bambergers were in the 1950’s when they functioned more-or-less as the Vox label’s house orchestra, can rest assured that by the 1980’s, they were a much more impressive group. Levine is almost as grand as Eschenbach, but his crisp textures and rhythms keep his energy from flagging, despite some broad tempos. And, not surprisingly, the playing of the Berliners yields to no one. Louis Fremaux and the City of Birmingham Symphony made an intense recording for EMI in the early 1970’s, and though it is a touch overwrought, it is vividly dramatic. Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra made at least three stereo recordings of this work, with the finest being the first, on Columbia, with E. Power Biggs playing the organ part. Ormandy’s plush sound is married here with a fairly high voltage which keeps the performance rolling along. The later RCA and Telarc remakes grow more stolid and dull, even though the sound improves markedly from the dry recording Columbia made.

To be avoided at all costs is the Karajan/Berlin Philharmonic recording on DG, which is a slow, turgid, harshly recorded affair with an out-of-tune dubbed-in organ. The Berliners can be heard in far more flattering (and far more inspired) light on the Levine recording, from some years later. The Bernstein/New York Philharmonic recording is, surprisingly, only marginally better than the Karajan. One might expect Bernstein to cut loose and enjoy the brilliant surfaces of the work, but instead he sought to make it “profound” and Germanic, leaving the listener awash in a sea of pretension. Similarly disappointing is the recording by Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet, who might have been expected to nail a piece like this. But alas, he shows no great regard for the work, taking his time, letting the performance sag under its own weight. The two recordings I referenced by Jean Martinon are a little better, but Martinon’s EMI recording (with Bernard Gavoty at the organ) is awash in a sea of reverb that obscures all the details. The Erato recording (with Marie-Claire Alain at the organ) is much clearer and more vigorous, though still a touch heavy-handed.

For a little side note about Munch’s Saint-Saëns ‘Third’, there is a wonderful story that has circulated around for a number of years, and if it came to me accurately, then this is the place to retell it. The anecdote has it that the organ used in this recording had not been used for any orchestral pieces during the concert season when this recording was made, but no one had thought to check its tuning against the orchestra. The orchestra was spread out not just on the stage, but actually into the auditorium for this recording – a fact confirmed in the booklet – while the pipes to the hall’s Aeolian-Skinner organ were toward the back of the stage. The engineers had determined that with the three-track pickup, they would be able to get plenty of focus on the organ pipes, so that they could balance the sound, whereas Munch, positioned down away from the stage in the center of the house, would not be able to hear the organ much at all. The anecdote continues that on the first day of recording, they decided to start with the second half of the finale, which has the most extreme dynamics from soft to loud. Thus, they could establish the dynamic range for recording purposes. Allegedly, Munch and the orchestra charged into the music, while organist Berj Zamkochian tore into the organ part on stage. From his vantage point, Munch couldn’t hear the organ, and Zamkochian couldn’t hear the orchestra. And neither of them could hear the engineers falling off their chairs in the booth with helpless laughter when they discovered that the organ was about a half step out of tune with the orchestra, resulting in a comical monstrosity of sound. After summoning their wits, the engineers called down and stopped the performers, postponing the session until a technician could tune the organ to the orchestra’s pitch. I don’t know if this story is true or not, but it is easy imagine how such a fiasco could have occurred!

The fillers on the Munch disc are three-track recordings from 1956. The recording of ‘La Mer’ is fairly well known, and was widely circulated, but it is not a great performance. Debussy and Ravel are often paired as “impressionist” compatriots, but the proof of how different their styles are is found in the fact that virtually no conductor is equally effective in the music of both composers. For instance, Claudio Abbado excels in Ravel but is much less effective in Debussy. Bernard Haitink is magical with Debussy, but his Ravel is often perfunctory. Munch’s Ravel is rightly legendary, but his Debussy seems more dutiful than inspired. The playing is stylish, and the recording is pleasingly colorful, but the music never sparks the fire of conviction in Munch that can be heard in the Saint-Saëns. Multichannel alternatives for ‘La Mer’ are not yet extensive, but the new Telarc SACD of ‘La Mer’ and the ‘Trois Nocturnes’ performed by the Cincinnati Symphony under Paavo Järvi is far preferable. (Check back soon for a forthcoming review of that disc, as well as an extensive discussion of the greatest recordings of ‘La Mer’.)

The other filler on this disc is a piece of showy exotica by Jacques Ibert called ‘Escales’ (“Ports of Call”). The piece had a bit of a heyday during the early stereo LP period as it shows off orchestral colors marvelously, as well as the skill of RCA’s early stereo engineers. Granted, the RCA recordings in Boston were never quite on the plane of their still-astonishing achievements in Chicago (more of which will be discussed in a forthcoming review of Fritz Reiner’s Dvořák ‘New World Symphony’ SACD, also from RCA’s “Living Stereo” reissue series). The Ibert recording, though, is quite felicitous in color, although both of the 1956 selections feature a slightly restricted range, having neither the rich bass nor the piercing highs of the 1959 sessions for the Saint-Saëns. Munch plays the Ibert showpiece for feisty thrills, making for a built-in encore to close the disc.

In the end, modern multichannel technology is ripe for a new recording of Saint-Saëns’ ‘Organ Symphony’, and with luck, one will soon appear that exploits the technology without turning into a “gee-whiz” dial-twiddling affair. Until that time, this three-channel release of Munch’s classic recording, as well as the stereo recordings by Paray, Dutoit, and De Waart will serve to remind us that great music doesn’t necessarily have to be “deep” or tragic. Sometimes it just plain rocks, and that’s good enough.

1 thought on “Boston Symphony Orchestra (Munch) – ‘Saint-Saens: Symphony No.3 in C minor, Organ’ An SACD review by Mark Jordan”