The idea of pairing minimalist-influenced works by the living American composer John Adams and the late Estonian composer Lepo Sumera is an intriguing one, if mainly as a study in contrasts. Adams comes across, in these works at least, as a composer who evokes the modern urban world, whereas Sumera uses a similar orchestral vocabulary to capture the feel of Nordic myths and desolate landscapes. Both composers use the repetitive gestures of minimalism as a departure point for adventures that would at times be better described as “maximalism”. In this recent hybrid SACD disc from Germany’s CCn’C Records, they both get passionate advocacy from Kristjan Jarvi, although his level of success in each piece varies.

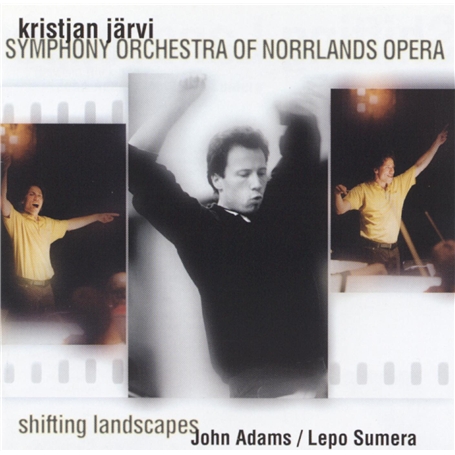

Kristjan Jarvi is the youngest of the amazing Jarvi musical clan – his father Neeme is an esteemed conductor of very wide repertory and is currently the music director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Kristjan’s brother Paavo recently began what promises to be an auspicious tenure with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Kristjan himself is conductor of two organizations – one is the Absolute Ensemble in New York, where young Jarvi has grabbed attention by refusing to limit his repertory to traditional pieces, playing everything from Bach to Zappa. His other position is in Northern Sweden with the Norrlands Opera. Kristjan leads with great enthusiasm, and one suspects that if Neeme is the no-nonsense sage of the family and Paavo is the poised and elegant one, Kristjan is the young firebrand. His urge to draw new listeners to classical music is a powerful one, and one certainly hopes he continues to have success in this area. But entering the arena of recording puts him up against some formidable competition.

The most familiar work on this disc is Adams’ ‘The Chairman Dances’, a “foxtrot for orchestra” inspired by one of the scenes in Adams’ opera ‘Nixon in China’. Adams wrote this tone poem before finishing the opera, apparently planning to use it in modified form in the final act, but ultimately Act III took on a darker tone, and only bits of the foxtrot were used, being metamorphosed to match the atmosphere. The tone poem, however, starts with the brisk sternness of Chairman Mao, but is distracted with the more sensual music representing Chiang Ch’ing (Madame Mao), reflecting her past as a movie actress. Energy and glamour unite toward the end of the piece, exultantly dancing away like a modern version of Strauss’ “Tanzlied” from ‘Also sprach Zarathustra’, with a final fadeout on percussion instruments to approximate the sound of an old 78-rpm victrola record winding down. Jarvi’s performance has so much brisk energy, it seems unable to relax into the more sultry parts of the piece, making the earlier recording by Simon Rattle seem a little staid. But, in the final analysis, no other recording has surpassed the first one, made in the mid-1980’s by Edo de Waart and the San Francisco Symphony for Nonesuch. De Waart recognizes the work’s need for glamour. Jarvi’s orchestra plays very skillfully, but in music so dependent upon sheen, they are ultimately outclassed.

Adams’ ‘Fearful Symmetries’ depends less on shine than on the relentless build of energy. It uses minimalist patterns to unleash a fearsome momentum. Whereas most minimalist music is calming, inducing a trancelike state in some listeners (and sleep in others), this piece is a seething late-night cityscape, albeit one with a wicked wit. It starts with a gesture very similar to ‘The Chairman Dances’, but instead of nostalgia, here one finds an obsessive world on the verge of careening out of control. Where in the other piece Adams uses saxophones suavely, here they are “lounge lizards”, cynically slithering around in the foreground of the ensemble. Each time the energy subsides, it soon rebounds to ever more frantic heights. The final build-up is destabilized by unexpected dipping into mixed meters, and just at the point when it seems the whole structure is about to collapse, it suddenly vaults up onto a quiet plain of glittering starlight, and fades out peacefully. Jarvi’s main competition here is with the original first recording, made in 1988 by the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, led by the composer himself. Jarvi’s recording is a minute faster than Adams’, which might not seem like a significant difference in a piece almost a half hour long, but it does matter. Whereas one might expect the timing to reflect Jarvi’s defter handling of the orchestra (Adams is a composer first and foremost), it seems instead to show a miscalculation. Jarvi’s energy is so frenetic at the beginning, detail gets lost, along with much of the piece’s sly wit. The spacious recording does not give much time for detail to register before it is swept away. Moving into the quieter middle of the piece, Jarvi lets the tempo sag a little, which stalls the forward flow. To get back on course as he moves toward the final peak, he accelerates so much the orchestra has to scramble, more approximating the notes than playing them. Thus the climax doesn’t pack the wallop it should. In contrast, Adams resists the urge to push too hard too early, thus he doesn’t lose momentum later on; and toward the end, he doesn’t let the careening energy get away from him, so the climax, and its resultant transcendence, feel utterly inevitable.

The least familiar work on this disc, for most listeners, will be Lepo Sumera’s ‘Symphony No. 2’. Though this is the first Sumera work I have heard, I hope to hear more. One could think of this piece as being freewheeling minimalism crossed with Nordic folk music. Though the shadow of Sibelius still lies over the composers of Scandinavia and the Baltic Republics, Sumera’s music harkens back even further, to bardic traditions dissolving into the mists of time. Though no program is specified, Sumera’s ‘Symphony No. 2’ is powerfully evocative music. The first movement opens quietly, featuring compelling melodic material on solo harp. The movement grows to craggy, violent heights before it subsides into the uneasy second movement. The last movement features a folk-influenced athleticism, but also a complex interplay of emotions as it strives to counter the dark threats of the first movement. It finally leads us back to the bardic harp music, which fades out gradually, letting the tale continue on in the listener’s mind. Jarvi is triumphant in this work. In these days of multiculturalism, it seems unlikely that this is because Sumera and Jarvi both come from Estonia – after all, Jarvi has spent more of his life in America than in the land of his birth. Perhaps it has more to do with the fact that this work starts quietly and builds its mountains explosively and quickly, and depends less on maintaining a precarious balance. Balance and reserve are things that Jarvi can develop with age. Hearing him in Sumera’s stirring piece proves that he is a major talent.

The recorded sound of this disc is good. It is spacious, which suits the Sumera piece better than the Adams pieces, which are less rough-hewn and more fastidious in orchestration, showing the difference in the composers’ influences: Sumera, after Sibelius and folk music; Adams, after Ravel and Mahler. The tendency of the sound to be a bit blurred in places seems to be a byproduct of the surround presentation. It is a rather aggressive mix, with more sound coming from the rear channels than you would get in a live concert hall. Again, that spacious “epic” sound, though somewhat artificial, is effective for Sumera’s craggy, misty landscapes. Adams’ urban world needs instead a closer, more precise sound image.

In sum, the Adams performances are interesting, but by no means displace the finest. The performance score awarded is an average, judged individually the Adams rates 60% and the Sumera 90%. Therefore I would recommend this disc for the Sumera work, and hope to hear more of his music from this source in the future.

Jarvi