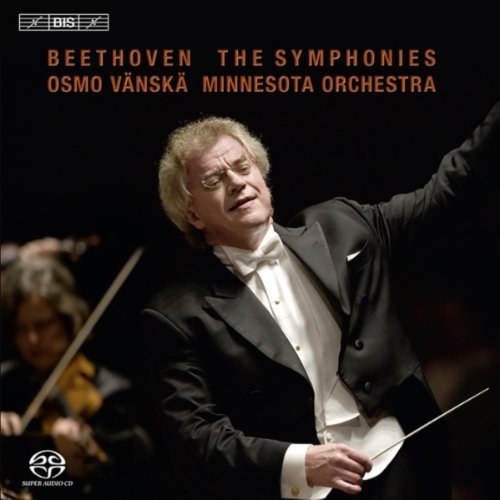

There was a time, not so long ago, when almost every new Beethoven recording which was released had a sense of routine to it. But the last decade or so has found players and conductors of all ages digging deeper into these warhorses to find the depths that still lurk behind even the most familiar phrases. The young Finnish conductor Osmo Vänskä is now recording an entire cycle of the Beethoven symphonies with the Minnesota Orchestra, the orchestra he has been revitalizing ever since he was named music director in 2003. He proves to be a committed Beethovenian of vision, energy, and power. Between this cycle and the Haitink cycle on LSO Live, we may well find ourselves on the receiving end of the best Beethoven cycles in many years.

Vänskä starts with a bang and directs an energetic though never brash rendition of the ‘Allegro con brio’ first movement of the ‘Eroica Symphony’. Amazingly, Vänskä manages to corral enormous amounts of energy without ever turning the whole affair into the nearly brutal (but always exciting!) sort of pummeling in which Arturo Toscanini specialized. Vänskä and his Minnesotans display a range of concentration which rivals the fine Szell/Cleveland stereo recording from the late 1950’s, but at the same time Vänskä never lets things sound as rigid as Szell. In other words, the energy here is coming from the players willingly, as opposed to the fear-o’-God despotism practiced by Szell, Toscanini, Reiner, and other such maestros who grew up believing in the ‘Great Man’ philosophy of public life which so disastrously led to the cult of personality madness which still plagues the world today. Osmo Vänskä points the way to the future: He hardly draws any attention to himself, yet the performance is never impersonal or cold. He loses himself in the process of leading the orchestra to a new level of involvement with a great composer’s genius. He also goes to the trouble to notice all of Beethoven’s detailed score markings, even the inconvenient ones. That alone keeps Vänskä from sounding like the average performance. But wait, there’s more! He particularly favors a hyperactively wide dynamic range from punchy accents and climaxes down to whispered quiet parts so low, one wonders if the back desks are even playing. Vänskä finds an ideal balance between crispness and weight. Comparatively, some listeners may find the explosive energy and whip-crack style of David Zinman’s ‘Eroica’ on Arte Nova more to their liking, while others may lean toward the silky sleekness of Abbado’s Berlin Philharmonic outing from a few years back. Others may prefer the historically informed, yet simultaneously weightier renditions of Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe (on Teldec/Warner) or Sir Simon Rattle with the Vienna Philharmonic (on EMI), but I find that only Vänskä combines all of these flavors into one harmonious blend. He has crispness, without becoming hyper and fussy. He has elegance without becoming overly refined and enervated. He appreciates the weight of the first two movements, yet is able to commit fully to the joyous freedom of the last two, unlike Harnoncourt or Furtwängler. And he has a sure-handed power which never threatens to break down into the didactic episodes that constantly sidetrack Rattle. I have yet to hear the new Haitink, though. If any recent recording could give Vänskä a run for his money, that will be the one, for as Haitink recently showed in his wonderful LSO Live recording of Beethoven’s ‘Symphony No. 7’, he has rethought his approach to Beethoven and lightened up his orchestral palette, allowing the music greater room and spontaneity.

Like most modern conductors, Vänskä keeps the “Marcia funebre” second movement of the ‘Eroica’ from becoming its own separate music drama, as it does in the epic performances of Furtwängler (DG or EMI), Fricsay (EMI), and Bernstein (DG). I’m happy to report, though, that he does not turn his baton into a cattle prod as Gardiner, Norrington, and Zinman have a tendency to do in their metronome-obsessed performances, bringing the movement in at a jog-trot pace. Vänskä allows it room to develop into the towering masterpiece it is. He balances the expressive and powerful with the need for momentum and forward movement, counting on his players’ inspiration to carry the day, which indeed it does. The level of personal involvement and inflection from the players is very high. And this is of course the secret of great conducting, no matter the means: These players aren’t playing Osmo Vänskä’s ‘Eroica’. It has very much become the shared property of all the players (plus Vänskä). Thus it gains in intimacy and coherence, capturing more of the feel of a theatrical piece with ensemble cast, instead of sounding like a horde of bored robots following the whims of some megalomaniac. Fifty years ago, the ensemble approach was best exemplified by George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra, and there can be no greater praise for Vänskä and the Minnesota Orchestra than to talk about them in the same breath. I do wish he had let the musical line “fall apart” a little more during the final disintegration of the funeral march, but his incredibly withdrawn, whispered manner is effective, too. My problem is that I’ve never been able to banish memories of the agonized way Bernstein slowed and hung the final chords in the air in his 1980 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic. Hardly defensible from the point of the view of the score, Bernstein’s maneuver is nonetheless the sort of theatrical coup which proves that sometimes even the composer must step aside to let through a lightning bolt of pure genius. Let us just hope as the years roll by that Vänskä will by canny enough to allow that to happen once in a while in his own performances without letting such gestures get the upper hand and distort his music making (which they sometimes did with Bernstein, though often to glorious ends).

Vänskä’s “Scherzo” starts as lightly as dandelion fluff, spinning past before one even quite realizes the movement is underway. The first gruff outburst plants us in perfect Beethoven “ungeknopft” (“unbuttoned”) territory: Boisterous rough-housing of the most divine sort. The movement central trio features sculpted horn calls played with greater йlan than any other recording I’ve heard, and I’ve heard a lot. Vänskä properly leaves a pause before plunging into the “Finale,” as called for in the score, but not always honored by conductors. Vänskä again paces the movement judiciously, allowing elbow room, yet never letting the line sag. In the great ‘Hungarian Variation’ at about four minutes into the movement, Vänskä leads the attack with plenty of energy, though he doesn’t push it to quite the frenzied height that some do. Instead, he concentrates on sorting the textures so that the main theme always remains in focus. He has the orchestra play the sudden drop of volume on the final chord of the variation as written, in tempo. This is often not the case, as confused conductors try to turn this most shocking of Beethoven’s jokes into something metaphysical by slowing it down and stretching it out, or smudging some of the chords (as both Rattle and Harnoncourt do). Quite simply put, Beethoven sets up the listener for a big pratfall by building up to a climax, only to pull the rug out from under one’s feet on what “should” be a big final chord, instead replacing it with a timid “boop.” Vänskä gets the joke and executes it adroitly. Afterwards, building toward the true climax of the movement, Vänskä again sorts the textures, keeping the most important lines highlighted, thereby allowing those themes to pull the movement to its peak. The performance’s authority is easy and self-assured as the horns scale the heights, for once blessedly sparing us the traditional slowing down as the horns reach up for the dominant at 8:42. This helps transfer extra energy and concentration into the sudden, tense shadow which engulfs the music before the coda erupts in a blaze of glory to close the symphony with several triumphant jabs, again led by the horns who are here punchy and pungent, just as they should be. Even here one can note Vänskä’s attention to detail, as he lengthens the final chord, as written in the score.

Going into the Beethoven ‘Symphony No. 8’, Vänskä and friends remain quite effective, even if not quite on the same plane as the Eroica. In general, the performance moves along fairly quickly, but with a warmth and fullness of sound that keep it from turning brash. I must say, though, that I don’t mind brash in this work. The three greatest performances of the ‘Eighth’ – Scherchen (Westminster), Casals (Columbia/Sony), and Zinman (Arte Nova) – get very brash indeed. Those three performances find wells of adrenaline to fuel this often-overlooked symphony, proving that with the right commitment it can stand toe to toe with any other Beethoven work. Casals takes the prize for the first movement, burning with a compelling concentration and forward momentum that knocks everything out of its way. Zinman and Scherchen are hot on his heels with fast, energetic renditions that only just barely miss the inevitability of Casals and the Marlboro Festival Orchestra. Vänskä is a degree more easy-going, though his energy level is high and his players keep textures brisk enough to forestall the sort of comfortable, sleepy warmth that overcomes too many performances of this music. Vänskä’s inner movements are shaped effectively, again just a degree broader than some of my favorites. Vänskä shapes the rambunctious finale at a moderate pace. The inescapable favorite for this movement, however, is the old Scherchen recording from 1958, with the London Philharmonic. The tempo is unbelievably fast (faster even than Beethoven’s well-nigh impossible metronome mark!) and the players are on the edges of their seats keeping up with Scherchen’s mad rush. This tension and brilliance give Scherchen’s Westminster recording an adrenaline boost that no other recording can match. Interestingly, after his first movement whirlwind, Casals opts instead to pace the finale more slowly than normal, so that every note can be heard, with the players channeling their energies into intensity of attack, much like the finale in Casals’ recording of Beethoven’s ‘Seventh’. Vänskä is less extreme here, and is thus a little less riveting, though he remains far more lively and compelling than the average performance of the finale. Overall, in the ‘Eighth’, Vänskä yields to Scherchen, Casals, and Zinman. But that still means he has bypassed some of the greatest names in recorded history: Bernstein, Toscanini, Klemperer, and the lot. And the recent live recording of Beethoven’s ‘Symphonies Nos. 7 and 8’ from Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic (available for download from Deutsche Grammophon) isn’t even in the running against Vänskä’s ‘Eighth’ or Haitink’s ‘Seventh’.

One clear advantage the emerging Vänskä cycle has over the concurrent Haitink production is recorded sound. Both are in high-definition multichannel sound, but the Haitink is hampered by the dryish acoustics of the Barbican Centre in London, a condition increased by the sound-soaking qualities of humans present during a live concert recording. Technicians have tweaked the hall itself in the last few years, as well as the LSO Live recordings, to improve the basic sound of the Barbican, but they wisely kept the reverb turned low in Haitink’s recording, because music originally written for smaller concert halls than the modern variety can turn into mush if it gets swamped by an over-resonant acoustic. The Minnesota Orchestra, however, is blessed with a much better concert hall, and the skillful engineers from BIS have extracted a recorded sound from it that even surpasses the highly admirable Reference Recordings made there by Dr. Keith Johnson over the last decade or so. Indeed, these new recordings are so colorful, warm, yet full of texture, that I feel compelled to award them a rare 100% rating, as there are no audible flaws. There is an excellent three-dimensional sense of the orchestral layout, with cellos to the left and second violins to the right as they would have been in Beethoven’s day. The recording’s directionality and stage depth are ideal. Listening to the DSD multichannel layer of the Super Audio Compact Disc, I found the hall atmosphere to be perfectly balanced, with the ambiance at just the right threshold for quiet chords which follow punchy accents to seemingly coalesce out of the leftover wash of sound. The surrounds decisively bring the listener into the room, without the sort of annoying overuse which could make for acoustic bounceback from the surround channels. Rather, the sweet spot is found where the ears can hear the sound of chords traveling from the stage back through the hall, past the listeners, and into distant corners of the hall. In the stereo layer of the high-resolution DSD program, the recording keeps a yeasty freshness to the woodwinds and a welcome burr on the brass accents, though the distancing effect of the stereo layout removes some of the immediacy of the performances, lessening the impact of a recording that was very clearly tailored for multichannel listening. The redbook CD layer is another degree removed in liveliness from the high-resolution layers, though of course the liveliness of the performance itself keeps this disc competitive with the finest other recordings. In short, for performances and recorded sound this fine, there’s no reason to hesitate. The outstanding question at this point remains, though. Who is going to record the great Beethoven cycle of our day, Bernard Haitink and the London Symphony or Osmo Vänskä and the Minnesota Orchestra? I have a feeling I’m going to want to have both at hand: Haitink for his wisdom and simplicity, and Vänskä for his energy and attention to detail.