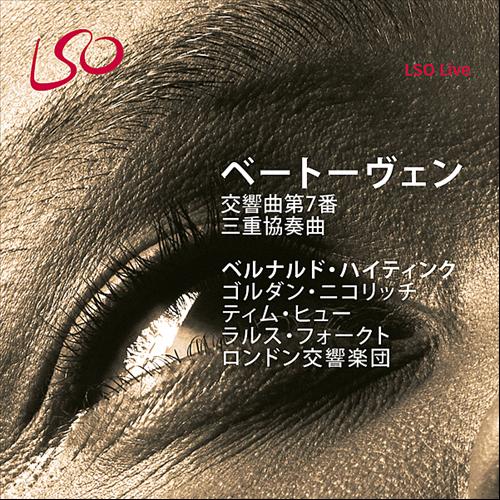

Watch out for the quiet ones. They’ll get you when you least expect it. Bernard Haitink is a quiet one, and always has been, doing his work as conductor and orchestra builder in a straightforward, unglamorous way for over a half century now. I’ve found myself too frequently over the years looking past Haitink at more colorful personalities. But it’s always at that moment when I’m just about ready to dismiss Haitink as bland that he sneaks in something unexpectedly pulse-pounding. He has done it once again with his new Beethoven ‘Seventh’ with the London Symphony on LSO Live. On the surface, such a vital piece might seem unusual territory for Haitink’s quiet mastery, but the secret of that mastery is that he knows when to lead and when to give the players free rein. The result here is one of the most natural and joyous performances of Beethoven’s ‘Seventh’ I’ve ever heard.

Haitink holds the reins firmly in the introduction to the first movement, but, mercifully, he doesn’t try to make it into the Wagnerian mountain that far too many other conductors do. Instead, he lets it unfold at a flowing pace, balancing airy textures with a rich core of sound, particularly in the strings. Though the crispness of Haitink’s phrasing implicitly acknowledges an awareness of period performance techniques, the London Symphony players enrich that phrasing with the sonic warmth of modern instruments, providing a perfect balance of sound and scholarship. By comparison, Claudio Abbado’s 1999 recording with the Berlin Philharmonic was so sleek and airy as to seem positively ethereal, possibly an odd set of clothes for this boisterous symphony. Yet Abbado’s gossamer was preferable to Sir Simon Rattle’s fussy outfitting of the piece in mismatched clothes borrowed from both academia and tradition. Least satisfying of all is David Zinman’s hurried, impatient push through the introduction, marring his otherwise fine performance. I find Haitink’s naturalness preferable to any of them.

As the main body of the first movement unfolds, Haitink’s first surprise is his lightness of foot. He may be nearly eighty, but he obviously has plenty of life yet to channel through his performances. He sets the pace, but keeps a light hand on the wheel, allowing the London Symphony players to run with the pace with only the occasional nudge to direct things. One such place is in the forte punch shortly before entering the second theme group, which Haitink has the players hit with an ever-so-slightly delayed attack, giving it the feeling of a brake being applied. Immediately thereafter, they resume the build of joyous energy, playing with freshly sprung rhythms that make the movement irresistibly buoyant. Moving into the development, Haitink doesn’t push things to the delirious heights that Carlos Kleiber did in his 1977 recording for DG, but then again, Haitink doesn’t restrain his players, either, unlike Rattle or Abbado, nor does he keep a strict, mechanical beat as Zinman does. Thus the movement takes on a very free air. The London Symphony is famous for being able to do their finest performances after brief rehearsals, unlike, say, American orchestras who are accustomed to gradually delving into a piece during a whole week of rehearsals. Extra rehearsals add nothing for the fast-working Londoners, and the conductors who do best with this orchestra are those who can communicate what they want in a few brief gestures, and then can get out of the way and let the orchestra do it. Haitink does.

In the not-really-slow movement (marked ‘Allegretto’) Haitink lets the strings sing. Indeed, perhaps the true genius of this entire performance is that Haitink has made a subtle but crucial decision not to emphasize the rhythmic nature of the score. After all, any fool can see that this is above all else a rhythmic symphony. Yet when that obvious point is bluntly enforced, it can lead to such disasters as the NBC Symphony recording from the early 1950’s which Arturo Toscanini apparently led with a cudgel, it sounds so abusively joyless. (Listen to Toscanini with the New York Philharmonic in 1927 to hear him at his magnetic finest.) Haitink instead directs by the phrase, assuring only that the rhythms are played with natural spring, not literally as written on the page. (And experience in hearing this orchestra under less masterful conductors assures me that the sprung rhythms are Haitink’s work.) No extra emphasis is laid onto the rhythmic building blocks. They are allowed to do their work, powerfully yet flexibly, while Haitink shapes the phrases to build walls and finally a whole magnificent structure. This is most evident in the slow movement as he shapes phrases into whole paragraphs that carry you along, making the music seem both timeless and yet fleetingly brief.

Haitink’s phrase-building helps keep the third movement ‘Presto’ on track, but already here one can feel him loosening the reins, letting the players romp about and inject personal energy and characterization into these lines which so often seem churned out by less inspired orchestras like bolts of patterned fabric from a demented sewing machine. The trio finds Haitink painting a gorgeously pastoral picture without dropping to a slow tempo. At first glance, in fact, it may seem that Haitink is slower than recent historically-informed performances by David Zinman or John Eliot Gardiner (both of whom use the new critical edition of the score published by Bдrenreiter, as does Haitink). But Haitink is actually at the same pace. The difference is that he strings the notes together into phrases and paragraphs, giving the section shape and dimension it lacks in the less skillfully shaped performances.

And then Haitink brings down the riding crop and sends his players flying out of the gate for an excitingly fast finale. While Haitink is not quite as fast as Abbado or Harnoncourt, he has deftly paced it as fast as the music reasonably should go. Comparatively, Abbado and Harnoncourt both run into problems. Abbado cannot sustain his initial headlong pace, falling back to a slightly more comfortable tempo after the opening headlong rush. Harnoncourt, typically enough, is able to sustain his demonically fast tempo, leaving any sense of clarity and line shaping to fall by the roadside in his mad rush for the finish line. Haitink, true to character, runs the horserace like a quiet puppet-master behind the scenes, gently directing with just a tug here and there to channel this stampede down the right valley. The players sound as if they’re having a marvelous time, something far too rare among symphonic recordings these days. I would take this any day over the fussy lacquering of a Rattle or the air-brushed sleekness of an Abbado, accomplished though they are in many ways. And it beats the vital Zinman and Gardiner performances just by sounding more flexible, more alive, more human.

The final climax of the ‘Seventh’ is built masterfully, with first and second violins separated across the stage to fan the flames as Haitink lets the crescendo build to a joyous height. In the end, this succeeds in being the best Beethoven ‘Seventh’ recorded since Carlos Kleiber’s DG recording now available on SACD, and frankly, I like it even better than the Kleiber, although the recent DVD-Video release of Kleiber’s live 1983 performance with the Concertgebouw Orchestra remains the best. For further discussion of other past recordings, refer to the High Fidelity Review features on the Kleiber SACD and the Abbado DVD-A.

The fill-up on this disc is Beethoven’s affable, if not exactly riveting, ‘Triple Concerto’ for violin, cello, and piano. The old joke says that not all of a genius’ masterpieces are equal, and that Beethoven’s ‘Triple Concerto’ is the most unequal piece in his catalogue. At least we can derail that joke by briefly reminding everyone of Beethoven’s ‘Wellington’s Victory’, a “Battle Symphony” that belongs as low in the compost heap of musical detritus as we can bury it. And anyway, Haitink and his players take the ‘Triple Concerto’ at face value and have plenty of fun with it, relishing the grandeur of its wide-open spaces, yet rollicking in the Polacca-flavored ‘Finale’. Tim Hugh sings the cello’s slow movement song with arresting intensity, Gordon Nikolitch brings considerable flair to the violin’s dramatic moments, and Lars Vogt makes the most of the elegant piano part. Under Haitink’s direction, the orchestral parts are kept crisp and focused, contributing to this performance’s sense of purpose. Though I’ve dutifully listened to a number of recordings and performances of this piece in the past, this time I found myself unable to dislike it. Its inherent good nature combined with an enthusiastic, energetic performance make it quite an enjoyable dessert to follow Haitink’s glorious ‘Seventh’.

The folks at LSO Live are getting pretty sophisticated with their approach to orchestral recordings these days, crafting each recording to suit the nature of the music. Their recent Shostakovich Symphony No. 8 by Mstislav Rostropovich featured a more distant, epic microphone pickup, allowing the huge dynamic range of that work to register with full force. To add to the sense of desolation in the bleak, open plains of so many passages, they artfully sweetened the dryish acoustics of the Barbican Centre with some judiciously applied artificial reverberation. In sum, it made for an effective soundscape for that epic war symphony. But Beethoven’s ‘Seventh’ is a different beast entirely, written for much smaller orchestra, with its excitement coming not from large orchestral pyrotechnics but from the frolicking interplay of instrumental sections. Moreover, it is as sunny (for the most part) as the Shostakovich is gloomy, so the same recording approach would have been disastrous. Fortunately, LSO Live producer James Mallinson and engineer Neil Hutchinson are perfectly aware of that, and have created a wholly different sound world for Beethoven’s lithe symphony. Here the reverb is kept to a minimum, letting the Barbican’s natural clarity sort the textures of the work. Comparison to the Harnoncourt recording (Teldec), the 1963 Karajan (Deutsche Grammophon), or, in multichannel, the Carlos Kleiber (also on Deutsche Grammophon) shows how much intimacy and detail are lost in a lush acoustic. Echoey acoustics can have their appeal in Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’, the ‘Fifth’, and the ‘Ninth’, but the ‘Seventh’ is so dominantly rhythmical, its impetus can be sapped by a boomy recording. Here, the dry acoustics of the Barbican are ideal. One can hear what is happening, especially because it is happening, thanks to the ensemble spirit of the London Symphony, and the experienced hand of Bernard Haitink.

The DSD recording is in five channels, with no separate subwoofer channel, which is fine, as there are very few classical pieces that really need a separate, dedicated channel for low-frequency effects. The microphone placement is also much closer and more intimate than it was for the Shostakovich. Indeed, quite a lot of primary information quickly arrives in the surround channels, just because there is not a lot of reverb. But this has the effect of bringing the listener even more closely into the performance space, which is important, because Haitink’s focus is, as always, on the intimate interplay of the musical lines. Perhaps no major conductor can be more damaged by a poor recording than Haitink. If all this were submerged under reverb or given a more distant pickup, how much of this performance’s playfulness and chamber-music-like sense of dialogue would be lost? My guess is quite a lot.

Indeed, when I turned to the 2.0 channel stereo SACD mix, I was already aware of the “distancing” effect of removing the surround channels. Though still a fine recording, and though still closer in perspective than most, it was less inviting. The regular compact disc stereo layer slightly emphasizes the astringency of the Barbican’s sound in the typical flat and glassy manner of red book CD’s. The stereo SACD layer dramatically increases the warmth of the sound, and the multichannel program truly brings in to life. The final sound of the Barbican is dry enough that I found myself wanting a tiny bit more sense of back-of-the-hall sound, therefore I have rated the recording at 90%, while at the same time acknowledging that it is probably as fine a recording of this piece as could be made in the Barbican.

In the ‘Triple Concerto’, the engineering is especially impressive, because it avoids the two pitfalls of multichannel recording with soloists. First, thank God, it doesn’t give the soloists a bad case of TFPSS (Twenty-Foot Pop Star Syndrome) unlike most modern recordings which highlight the soloist as in a pop recording and relegate the orchestra to the distant background. And second, in the surround mix, the soloists are not artificially thrust out even further, due to the three-dimensional nature of surround sound. LSO Live deserves copious praise for this, for even companies as fine as Telarc have had problems with this issue. Rather, on both counts, the soloists are kept in front enough to be heard, but also integrated into the full, rich orchestral texture with grows up around them. The interplay among the soloists and with the orchestra thus flows naturally back and forth, making this piece a more satisfying listening experience for me than it ever has been before.

In short, this is another fine release from LSO Live, featuring an ingratiating and involving performance of the ‘Triple Concerto’ and a performance of the Beethoven ‘Seventh’ that is among the finest things Bernard Haitink has ever done. Though one can occasionally hear audience noise in these live recordings, it is minimal, and the dominant contribution of the live status is merely the electricity and sense of occasion that only comes with live performances. No applause is included for either work, though I wouldn’t have minded hearing it after such extraordinary performances.

In sum: Hallelujah! The art of Beethoven conducting is alive and well.