Johnny Smith came on the scene in New York in the late 1940s, after a stint in the Army, where he learned to play a number of instruments. While “paying his dues” and struggling to make a living, Smith roomed with a number of guitarists who went on to be famous in their own right, including Sal Salvador and Jimmy Raney. Thanks to his musical abilities, including the ever-important skill of sight-reading, he wound up on the staff of NBC as a studio player, playing a wide variety of musical styles from country and western to classical, and everything in between, and lots and lots of commercials. By night, he sat in with all the jazz greats on New York’s famous “Swing Street”, 52nd Street.

At this same time, tenor saxophonist Stan Getz was also working as a studio musician at NBC. In 1952, he and Johnny teamed up for several recordings for the new Roost label, including Johnny’s one big hit, Moonlight in Vermont. The tune opened to Johnny playing the now-familiar six gorgeous chords. What only guitarists understood was that those beautiful chords were nearly impossible to reach for the player with average-sized hands. They were chords normally played by pianists–an easy task as the keys are close together and do not require long reaches, and it allows a player to easily hold one note in that chord while transitioning to the next chord. Ask any experienced guitarist, and they’ll tell you those chords are impossible to reach, due to the way a guitar is tuned (the strings are tuned three or four whole steps apart, EADGBE, from lowest to highest). Johnny figured it out and did it with such nonchalance that it made it sound easy. This hit record propelled Johnny Smith to the very top of his field, and afforded him the opportunity to record another 15-20 albums for Roost between 1952 and 1960, and another 3 for Verve between 1962 and 1967.

Johnny Smith was born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1922, to working-class parents. His father worked in a local steel mill until the Depression caused it to close. The family migrated up the east coast for several years, ultimately winding up in Maine, which was a truly foreign place for a young southern boy. He taught himself to play guitar, and by his early teens, was good enough to work professionally in a hillbilly band, where he made the princely sum of $4.00 per night (big money in depression time). Johnny later learned to read music and even taught some during those years. He began listening to jazz, and by his 18th year, was playing jazz almost exclusively, influenced by players like Les Paul, Charlie Christian, and Django Reinhardt.

He also learned how to fly while a teenager, and had hoped to use those skills when he got drafted into the Army Air Corps in the early days of WWII. Unfortunately, his vision wasn’t up to the high standards, and washed out. He did maintain his civilian license, and flew his own private plane regularly into his 70s. He was transferred into the Army Air Corps band, where it turned out they don’t use guitarists. He was handed a trumpet method book and was told to learn all he could over the next two weeks (it was that or the infantry). He emerged with sufficient abilities to remain in the band, playing trumpet by day, and guitar in off-post jazz bands by night. At the end of the war, he returned to his home in Portland, Maine, and tried to decide what to do next. After entertaining several offers, he chose to go to New York to seek his fortune.

While at NBC as a staff musician, he worked on as many as 35 shows a week, including a job as a guest soloist with the NBC Symphony Orchestra under famed (and volatile) conductor Arturo Toscanini. As stated before, by night, he worked the clubs along 52nd Street, and worked with the best players of the time (unfortunately never recorded) including Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, and others.

One of his most famous compositions was a reharmonization of Softly, As In A Morning Sunrise, which he titled Walk, Don’t Run. The rock and roll hit of this tune by the Ventures, as well as a lesser hit by Chet Atkins, in the early 1960s, royalties from this tune helped pay the bills while he recovered from a fishing accident, where he sliced part of one of his fingers off.

Like many popular musicians, Smith burned the candle at both ends, working the studios from morning until night. He’d go home and nap for a few hours, before hitting the Manhattan clubs from 9PM to 4AM, only to start all over again the next morning. His wife died in 1958, which caused him to reassess how he was living his life. He had a four year old daughter, and upon the advice of several experts, he gave it all up and moved to Colorado Springs, where he retired from active playing, and opened a music store. He remarried a few years later and had two more children.

Smith had several “artist model” guitars named after him over the years, including the Guild Johnny Smith Artist Award model, which, because Guild changed a few of his specifications, he demanded his name be removed. The Artist Award model remained in Guild’s catalog until 2006, when Guild’s parent, Fender, reduced the number of Guild models, including all of their custom-built archtop models. In 1962, Gibson came out with a Johnny Smith model, which remained in the catalog until 1992, when Johnny signed an endorsement agreement with Heritage (guitars built in the old Gibson factory in Kalamazoo, MI), at which point it was renamed the LeGrande, and it is still in the catalog today. When players bought a Johnny Smith model from Gibson, for a slight extra fee, the guitar was shipped to Smith’s music store in Colorado Springs, where Johnny did the final setup himself. It is also notable that for the majority of Smith’s Roost recordings, he used his prized D’Angelico Excel guitar. It was not until the Verve recordings of the 1960s, that he played his signature model Gibson.

As the years went on, he was occasionally coaxed out of retirement to perform. He was the featured guitarist for Bing Crosby’s final tour in the late 1970s, and he made a tape of 12 acoustic solo masterpieces, issued by Concord Jazz, with an additional 12 solo tunes by legendary guitarist George Van Eps in the 1990s, on a CD simply titled Legends.

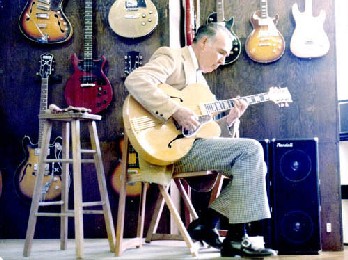

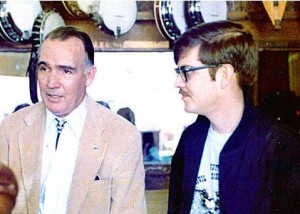

He occasionally did guitar clinics for Gibson in the 1970s, which is where I met him (was I ever that young or skinny?). Back in 1978, I was in the US Air Force on temporary assignment to Davis-Monthan AFB, in Tucson, Arizona (overhauling radio systems at Titan II ICBM sites). As a jazz guitar nut even then, I was thrilled beyond words to discover that famed guitarist Johnny Smith would be hosting a Gibson-sponsored clinic at a local music store. I took one picture of Johnny when playing (trying to keep my loud, clunky Canon SLR camera quiet). I took another few of him after the clinic, surrounded by admirers. One of those admirers noticed I had taken a shot of him standing next to Johnny and asked me for a copy of the shot. I agreed but only if he would take one of me with Johnny. Here’s the part I’m not exactly proud of: the picture was taken, but without Johnny’s approval or acknowledgment. I was just standing there looking at him, as he was busy talking to a bunch of other folks, and I didn’t want to interrupt… My boorish behavior probably reinforced why he wanted no part of me or my family (my uncle, the late Andy Nelson, as a Gibson salesman and clinician, knew Johnny very well and was strongly influenced by Johnny’s playing style–Andy was also a very brash, in-yourface kind of a person, as a salesman of his era would be, which probably made Smith somewhat cold to Andy–understandable, as Johnny was a very quiet, introverted southern gentleman who was probably uncomfortable around Andy’s bigger-than-life persona). Johnny, if you ever read this, my deepest apologies for my poor behavior–I really was brought up better than that!

He sold his music store in the 1990s and enjoys fishing, and visiting and having a “taste” with old friends in the music industry. I was pleased to read a story in a recent Just Jazz Guitar magazine that Johnny attended a jazz guitar clinic in England, and actually played a few pieces, which dispels the statement he has often made that his guitar is under the bed and that’s where it’s staying.