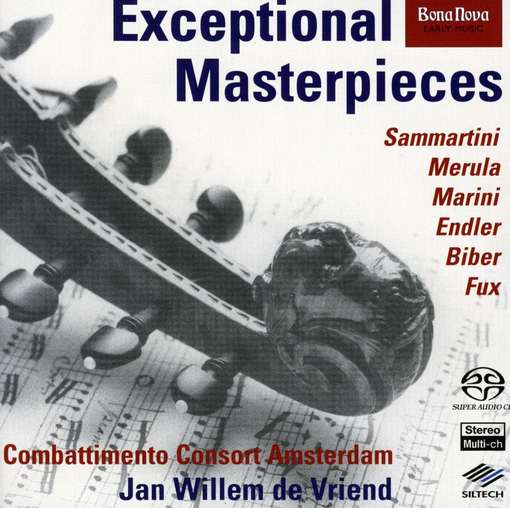

Fame is fickle. But after nearly three hundred years of obscurity, it seems to be coming at last to Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber. Although fairly well known in his day, his music drifted out of favor in the 1700’s as the intelligentsia gravitated towards bright and logical composers of the classical era. To them Biber must have seemed a real crank, moody and prone to unpredictable outbursts of passion. But in recent years, his star has once again risen. Biber first hit the radar of many classical listeners in 1965 when Nikolaus Harnoncourt recorded the now famous ‘Battalia in D’, a programmatic romp that includes pages that wouldn’t sound out of place in Ives or Bartok. On the other hand, Biber still wouldn’t have flown if his music didn’t strike a resonance in listeners. After all, if the late twentieth century saw a great swelling of interest in the music of Gustav Mahler, then it seems only natural that it would be accompanied by a rise in interest in the composer who could best be described as the Baroque Mahler. Biber is indeed the most commandingly interesting composer on this fine hybrid CD/SACD from Bona Nova entitled ‘Exceptional Masterpieces’, but the other works performed here by the Combattimento Consort Amsterdam don’t lag far behind. The stated intent of the disc is to present some lesser known but amazing pieces from the ensemble’s repertory, and they deliver on that promise.

The disc starts off with a pair of jaunty pieces by Tarquinio Merula, one of the first composers to write in an advanced, virtuoso manner for violin. Merula seems to combine the strong rythmicality of late Renaissance music with the virtuosity and adventurousness of the early Baroque. Next up is a doleful “Passacaglia” by Biagio Marini, a comtemporary of Merula. The piece is expressive, even agonized in places, with several harmonic surprises along the way, not least of which is the unexpected sigh of relief that lands in a major key during the closing moments. The next piece on the recording is a ‘Concerto in C’ for violoncello piccolo and strings by Giovanni Battista Sammartini. This is one of the very few pieces written for the violoncello piccolo, which is basically a miniature cello. Sammartini stood astride the indefinite border between the Baroque style and the newer Classical style, and this piece makes it clear that he functioned as a bridge between Vivaldi and Haydn. The solos are sparklingly played by Wouter Mijnders.

Another rare “miniature” instrument is the violino piccolo, featured here in the delightful ‘Rondeau in C’ by Johann Joseph Fux. Prior to this disc, I had heard the music of Fux a few times previously, and never warmed up to it. It seemed to me that Fux wrote in a very learned, contrapuntal manner that also happened to be dry as dust and about as interesting. Well, these performances prove that Fux was much more than an arcane scholar. This Rondeau for violino piccolo, bassoon, and strings starts off with great grace and charm, gradually growing very playful as the solos become more complex and adventurous, even dramatic. De Vriend’s playing of the violino piccolo part is quite delightful, even if he encounters the occasional passing difficulty keeping the miniature violin perfectly in tune. Without doubt, the difficulty in adjusting from regular violin to this smaller instrument had much to do with why it never caught on, except as a starter instrument for children.

Moving along, we come to the core of the program, which is Biber’s ‘Partita VII’ for two viole d’amore and basso continuo. The piece opens with a dark, arresting flourish. This Preludium continues on, though, to become consoling, and ultimately almost bright by the end. Typically enough for Biber, this emotional ground is covered in just over two minutes. The following Allemande is alternately dance-like and diabolical, setting the stage for the obsessive Sarabande that succeeds it. The central Gigue movement starts with a very haughty introduction before embarking on a rhythmical ostinato repeated over and over, hardly ceasing until the end. The fifth movement Aria promises relief by starting warmly and graciously, but it has a distressing tendency to slip into minor keys when you least expect it. Penultimately comes the short, lively Trezza movement, which does release some of the built up tension before we venture off into the Arietta with variations. Over its nearly seven-minute span, Biber charts a more gradual, if no more predictable course. The solemn theme slowly flowers throughout the variations until the tempo picks up and the piece rushes toward the end with great energy, only to suddenly pull back in its final moments into an otherworldly calm. Ingenious and wayward, this Biber piece alone would be worth the price of this disc.

But wait, there’s more! The longest piece here is the charming ‘Sinfonia No. 15’ by the obscure Darmstadt composer Johann Samuel Endler. It is notable for including a timpani part that requires the player to use five drums. So, unlike the usual restricted timpani writing used in the early 1800’s, Endler has his timpani going almost continuously, even in the slow movements. This is a very early symphony, and one can make out the structures of the nascent classical symphony. Indeed, had Endler stopped after four movements, had would have had a perfect early symphony, but one can hardly begrudge that such pleasant music continues on for two more movements, including a grand processional for the finale. Worth special mention is the trio of the third movement Menuet, where Endler has a pair of flutes dancing delicately over repeated notes on the timpani, accompanied by plucked strings. Truly delicious!

As a built-in encore, Combattimento Consort Amsterdam return to Fux to play his ‘Sinfonia a 3, a symphony in name only. Rather, this chamber piece is a picture postcard of a visit to Turkey, and the players enthusiastically tear into Fux’s Turkish folk-influenced tunes. The ending holds another store in surprise, as the players one by one stop playing, get up and leave the stage, presumably returning “home” from this excursion. The notes don’t say much about this, but it presumably is in Fux’s score, as it would seem more than a trifle eccentric otherwise. The last to leave can be heard closing the stage door behind him. I was a trifle surprised, however, that they didn’t make use of the multi-channel capabilities here to have the sound of the departing musicians leave the stage and walk past the listener to exit somewhere in the vicinity of the rear channel speakers. But, regardless, it is quite easy to imagine the door on stage that they use, as the SACD layer clearly locates it off to the left, twenty or thirty feet behind the playing area.

The CD layer of this hybrid disc is in its own right far better than the average CD recording. Much is made in the program booklet of the use of vintage microphones, tube technology, and pure silver and gold Siltech cables, and these elements presumably contribute to an unusually warm and rounded sound, some more than others. That’s not to say that it doesn’t have kick, because many passages leap right out of the speakers, but the sound is so warmly inviting, that I felt that I could listen to it extensively without experiencing any fatigue of the ears. That warmth and spaciousness is even more pronounced on the SACD layer of the disc, which solidifies the placement and texture of the instruments. The extra ‘air’ of the SACD layer of this DSD recording especially helps the more layered moments in the music. The multi-channel presentation diffuses the sound a little bit, but it is not greatly different from the stereo mix in impact. The rear channels are kept exclusively for ambiance. Very warmly recommended.

It’s not that I don’t like some other music of the composers presented on the CD but this selection in particular I found rather boring. Biber’s music quality is very uneven. You get masterpieces like Rosenkranz sonatas next to lots of rubbish which is deservedly forgotten. Same applies to the rest. I can sympathise with the urge of musicologists to dig and rediscover but not all they dug out is worth listening to.