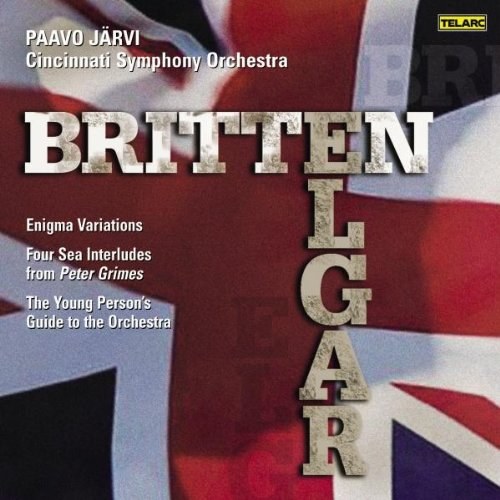

Sheer ardor may not be Paavo Järvi’s strong suit, but he has a scientist’s precision with the sifting of orchestral textures, and his new Telarc recording reveals details almost completely lost in the murk of other performances of these familiar orchestral works by English masters Benjamin Britten and Edward Elgar – even in performances led by the composers themselves. And Järvi’s sense of wonder never fails to make this music sound fresh and newly discovered. Best of all, Telarc’s engineers have either hit upon the perfect pieces for Cincinnati’s Music Hall, or else they’ve found some new insights to recording there. Whichever is the case, this release marks both Telarc’s and Paavo Järvi’s finest achievement yet in Cincinnati.

The disc starts with a performance of Benjamin Britten’s ‘Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra’, which is performed here without narrator (in which form it is sometimes billed more specifically as ‘Variations on a Theme of Henry Purcell’). The piece is designed to show off each section of the orchestra, and Telarc’s sterling recording helps it achieve that end better than any previous recording ever made. The high-resolution recording particularly allows one to savor the instrumental textures and flavors, particularly in the opening theme, which tosses fragments of melody from section to section, rendered as clear and directional in the multichannel program here as a tennis match. Yet even such felicities are secondary to Järvi’s insistence on finding the shape and personality with which this music is so packed. Indeed, the coupling with Elgar’s ‘Enigma Variations’ is particularly apt, because Järvi treats the Britten variations as character studies of the instruments themselves. Granted, in a fifteen minute piece, he can’t cover all the bases (though he does cover all the basses), but Britten has enormous fun finding new instrumental angles on Purcell’s grand, haughty theme, and Järvi’s Cincinnatians properly live it up. It is also worth noting that Telarc handily breaks the ‘Young Person’s Guide’ up into twenty tracks, allowing each sectional contribution its own track, and allowing the listener to dip in for highlights or to show off their sound system to friends. (The percussion sections are ideal for that purpose.) Indeed, there’s every reason to expect this to become an audio showroom standard. There is some artful highlighting of soloists and sections, but it is done more subtly here than, for example, the trombone glissandos in the recent Telarc/Cincinnati recording of Bartok’s ‘Concerto for Orchestra’, which were rather garish. Finest of all is the final fugue, which starts with one flute, then two, and gradually grows across the stage as more instruments enter and proceed to fill up the considerable acoustic space of Cincinnati’s Orchestra Hall. At the moment of maximum activity, the Purcell theme soars out above the frantic fugue, capping a glorious performance with a true sonic thrill. For collectors’ considerations, Britten’s own recording of this piece still offers unique insights, and other versions by Giulini and Andrew Davis are fine, too, but the Järvi really sweeps the field among current competition, and is unrivalled for multichannel listening.

Britten’s ‘Four Sea Interludes’ from the opera Peter Grimes continue the program with an icier edge. Though Britten himself, in his complete recording of the opera, was able to find greater warmth in these passages than most conductors, Järvi must be saluted for the alternately icy and silky textures he and his players bring. In particular, Järvi cuts through the textures of the final ‘Storm’ with an ice-edged dagger. The rigorous sorting of textures, allied with a slower than normal tempo, but more intense than normal playing style, gives the later pages an almost hallucinogenic vividness surpassed only by the last gasp of Leonard Bernstein’s greatness in concert with the Boston Symphony, caught on the wing during Bernstein’s final concert by Deutsche Grammophon in 1990. The ailing Bernstein was not on form everywhere else in the interludes, however, so Järvi soundly trumps him in the poise of his ‘Dawn’ and the fervor of his ‘Sunday Morning’. Perhaps Järvi is a touch fussy in the ‘Moonlight’ interlude, but yet the playing and recording are so fine, I find myself willing to take it in stride. Kudos as well to the Telarc recording team for not “juicing up” the final notes of the ‘Storm’ by turning up the reverberation. The musical impact, especially as handled here by Järvi, is sufficiently harrowing.

The first great recording of the ‘Four Sea Interludes’ was the early stereo outing by Carlo Maria Giulini and the Philharmonia Orchestra on EMI. Giulini’s suave poise and intense commitment wear well, but the recording itself hasn’t aged so gracefully. The later EMI recording by Andrй Previn and the London Symphony still sounds good, offering perhaps the most colorful and buoyant performance of the ‘Interludes’, though it, too, yields to Järvi’s brilliance. Among digital recordings of recent decades, the above-mentioned Bernstein is obligatory, but the Teldec recording by Andrew Davis and the BBC Symphony is an impressively focused and propulsive account of the work, though it misses some of the coloristic delights that can be mined from its textures. More problematic is the often impatient and underpowered Chandos version by the Ulster Orchestra conducted by Vernon Handley. Handley is usually a safe bet in British repertory, but as his Conifer recordings of Sir Malcolm Arnold’s symphonies showed, he can get too relentlessly focused at times. Both Handley and Davis yield to the present release. Indeed, Paavo Järvi has thrown down a gauntlet in this new recording, claiming the top spot and daring anyone else to try and match it for intensity and precision. It is interesting how Paavo Järvi stands far closer to the intense poise of a Horenstein or Giulini than to his father, the breezy Neeme Järvi. Maybe he gets it from his mother.

Indeed, Paavo Järvi is so fastidious; his relative youth rarely comes across in his recordings. His ‘Enigma Variations’, though, seems particularly youthful and virile, banishing the half-lights too often used to obscure the eccentric corners of Elgar’s world. It is only with the ‘Nimrod’ variation that Järvi widens the scope of the piece to something truly touching, which is shrewd planning on his part. Many performances wallow in emotion early in the piece, risking the loss of any chance at finding the momentum to hold these character studies together. It seems as if only Elgar himself in his 1926 recording with the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra had the sheer control over his players to push the intensity of the opening minutes of the work, and yet proceed to then shrug it off for a high-spirited romp through the next few variations. Järvi is less manic-depressive in approach, without seeming cold or distant. Indeed, Järvi is reminiscent of the earlier Decca recording by Sir Georg Solti in his forward thrust (the later Solti recording lacks the electricity and the risky sense of adventure of the earlier one). One could make an argument that Järvi misses something of the introspective affection shown by Sir Andrew Davis in his recording with the Philharmonia Orchestra done for CBS in the early 1980’s, but the Cincinnati performance is better played, with infinitely superior sound. Elgar’s rich scoring, combined with the warmth of Music Hall, but countered by Järvi’s precision and his orchestra’s brilliance, fit this music hand-in-glove. Listen to the perfectly sprung hesitations in ‘Dorabella’ floating away in the silence, or the pungent punch of the bassoons in ‘G.R.S.’, a variations that too often turns into a muddled mess. And the power and clarity of the timpani in ‘Troyte’ are something to behold. Nice to hear that after all these years, recording technology has finally caught up with Elgar’s quirky ingenuity, and is able to do glorious justice to this vibrant music.

Though very reserved, Järvi is quite affecting in the unnamed penultimate variation, where Elgar hauntingly evokes an image of his secret beloved leaving on a ship: The soft roll of the kettledrums with a couple of old British pennies placed on top evokes with peculiar vividness the gentle throb of a ship’s engines as it pulls away from the shore. The notes to this release confirm that Elgar’s quaint directions were followed precisely, even down to using large, antique British pennies. Even more touching is Järvi’s insistence that the low strings make a very slow glissando at 0:57 in the variation. But for sheer potent emotion, this variation has never been more potently rendered than in the vivid Philharmonia Orchestra performance conducted by Giuseppe Sinopoli in 1987 for Deutsche Grammophon. Sinopoli the psychologist pounced on this revealing moment, and made it the focal point of his expansive and idiosyncratic, though highly effective interpretation. Järvi remains more circumspect, transferring his attention to a brilliantly weighted account of the finale, better focused in its symphonic striving than any other I can recall since Elgar’s own recording. In sum, for character insight, the classic EMI recordings by Elgar himself, Sir John Barbirolli and Sir Adrian Boult are essential listening in the ‘Enigma Variations’; for warmth and emotional depth, turn to the Davis or Sinopoli recordings discussed above; and for incisive energy, Solti’s romp remains great fun. Among recordings of the last decade, Solti’s second recording (with the Vienna Philharmonic) is less vital than his earlier one; Mark Elder’s with the Halle Orchestra is compelling but at times overly fussy; and John Eliot Gardiner’s tetchy take should generally be avoided. But for a fresh look at these characters, combined with lucid direction, brilliant playing, and gorgeous sound, this recording is a must. I toyed with the idea of only giving a 90% rating on the ‘Enigmas’, but finally decided that it would be churlish to do this. Though I missed some of the emotional potency of Sinopoli and Davis, Järvi quite convincingly shapes the work to give his approach an inner balance and logic that make it compelling on its own terms. That’s what quality music-making is all about.

The 5.0 multichannel program of the Super Audio Compact Disc layer of this DSD recording is one of the finest orchestral recordings ever made. Cincinnati’s Music Hall is a tricky place in which to record, and though Telarc’s engineers have a lot of experience there, they have frequently been hampered by the quirks of how the hall reacts to different scoring and different conductors. With this release, they have hit a new plane of achievement (pretty much also achieved in the recent Bartok disc, with the single caveat mentioned above). The stereo SACD program features lots of impact, though it loses much of the exquisite directionality of the multichannel program, which lets one envision the placement of instruments as if you were in the hall with them. The compressing of the sonic picture down into two channels also increases the boominess of the sound, and some of Järvi’s hard-earned clarity is lost. That issue is magnified in the redbook stereo compact disc layer of this hybrid release (playable on all players). The textures are less vivid in standard resolution, and there’s even less sense of directionality. But the impact is still terrific, and, frankly, even just in low-resolution it stands head and shoulders above any other recording of these works, including other digital outings of recent vintage. In short: I’ve been teasing Telarc and Paavo Järvi for a while now, never quite willing to give out top marks, hoping that they would stretch that extra mile to achieve superlative results. This time around, I can’t deny that they’ve hit the bull’s-eye. This is an essential recording.